Whether focusing on a Soho hairdressers thriving in the 1980s or a grieving family desperate for communication in 2018, new British documentaries at the 2018 London Film Festival raise interesting questions about the power of reckoning with one’s past experiences.

The 62nd BFI London Film Festival ran 10-21 October 2018.

Several features look at the often strained dynamics of friendship and family, with a particular emphasis on how men handle personal efforts at self-reflection, restoration and rehabilitation. Through affecting commentary and displays of tender vulnerability, the films explored here deliver refreshing insights into both the emotional perspectives and artistic processes of their male subjects, with ever-present critiques of the political climates that have impacted upon their stories.

Evelyn

Orlando von Einsiedel, UK

With discussions of mental health awareness at the centre of public consciousness in recent years, Evelyn is a timely and poetic reflection on the tragedies of depression and the agony of grief. From the Scottish Highlands to the South Downs, the Von Einsiedels walk in memory of brother and son Evelyn – who committed suicide in 2004 – seeking an honesty and catharsis they have not yet been able to find. Siblings Orlando (directing here, and known for his 2016 Netflix documentary The White Helmets), Gwennie and Robin, along with their parents and family friends, spent a month filming their journeys over the lands Evelyn loved.

The accumulation of footage and conversation is quietly astounding, a documented attempt to finally speak together about Evelyn’s life and death, the trauma of which they have all buried. The film places a deeply emotional and necessary focus on male suicide, mental illness and the importance of vocalising and sharing the burden of suffering. Orlando himself must feel as much a subject of the documentary as its director; he certainly seems to welcome his own freedom of expression. He makes a conscious effort to talk to passing strangers who in turn reveal their own poignant stories, from an ice-cream salesman speaking about his own mother’s suicide to a former soldier whose friends took their own lives upon leaving the army. This uninhibited commitment to telling their own story and welcoming others to listen feels undeniably powerful and intimately raw.

Five Men and a Caravaggio

Xiaolu Guo, UK/China

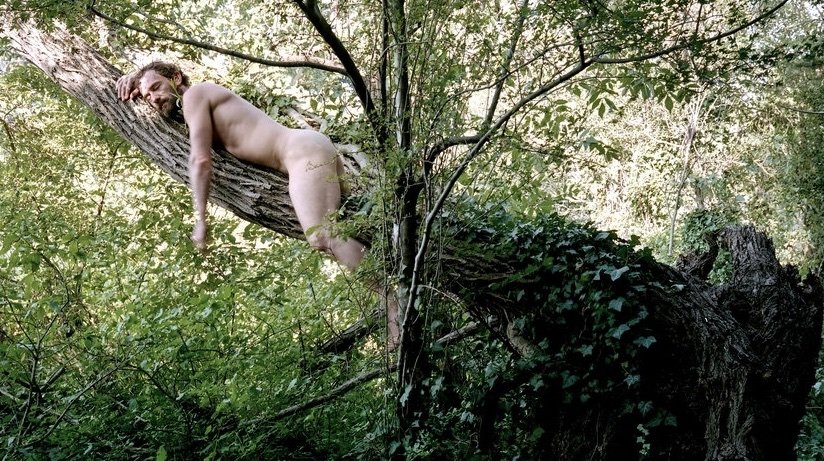

The latest documentary essay from Chinese filmmaker Xiaolu Guo closes the geographical gap between an artist in China, recreating Caravaggio’s portrait of John the Baptist in the wilderness, and a group of men in Hackney gifting the artwork to a friend for his 40th birthday. The titular five are introduced according to their creative and intellectual callings, opening with the Chinese painter. The friends in London, all non-UK nationals, are a photographer, a poet, a philosopher and a writer, and the film at once navigates their fundamental similarities and vast differences. These individuals seek new ways to express themselves, new challenges to occupy their days and new means of self-fulfilment, faced with the prospect of ageing and fears over inadequacy and dissatisfaction.

A sense of lost ambition, loneliness and even an air of pretension surrounds the four men in London. When the ‘philosopher’ attempts to touch up the Chinese artist’s Caravaggio reproduction, the often abstract threads of the documentary build up a more precise analysis of masculine ego and fragility. Balancing issues of originality and copy, age and youth, movement and stasis, Five Men and a Caravaggio is an engaging examination of lives on the brink of change, from the poet’s birthday anticipation and age anxiety, to the wider implications of Brexit politics for the friends living in the UK.

No Ifs or Buts

Sarah Lewis, UK

An in-depth portrait of iconic Soho salon Cuts, No Ifs or Buts has been in production for over 20 years. Documenting the rise of the business led by founders James Lebon and Steve Brooks, the film examines every corner of the Cuts community, from regular patrons and celebrity clients to staff struggling with personal demons in the changing social climate of London through the decades.

Filmmaker Sarah Lewis presents a striking vision of the city, weaving together a vast array of creative individuals and their various subcultures. Images of the Rockabilly scene, the New Romantics and Soho punks make for bittersweet memories of faded times, as the now heavily gentrified London landscape, and criminal underfunding in arts industries, hinder the expression of new creative groups.

The film also makes an important investment in detailing the mental health issues of staff, particularly Brooks, as well as his problems with drug addiction. The hairdressers joke that “madness or death” were the only routes out of the Cuts world, a sad truth for some within the almost entirely male workforce at the salon, who always sought to protect their close circle of colleagues and friends. No Ifs or Buts presents a stark portrayal of a rapidly changing scene, the joys and dangers of the successes found there, and the hurt inflicted on those who greatly cherished their role in building it.

After the Screaming Stops

Joe Pearlman, David Souter, UK

“What are you going to do when that screaming stops?” The question Terry Wogan posed to 80s musical phenomenon Bros at the height of their stardom inspires this film committed to following Matt and Luke Goss on their return to the UK for a revival tour. After encountering the highest peaks of fame followed by the harshest backlash with Bross, the Goss twins have lived their own lives at a distance from each other and their British roots. After the Screaming Stops delves into the personal grievances and insecurities that have been left uncommunicated and unshared for most of the brothers’ adult lives.

Directors Joe Pearlman and David Soutar tread delicately around the issues between the brothers, but ultimately encourage a highly revealing and open discussion. Attempting to make peace with one another is challenging, as arguments arise from everything to sarcastic comments to changes in tone of voice, but the two men speak with an emotional honesty and engage with their own frailties. What emerges from the mire of the Bros downfall is a story of regeneration and renewal. The filmmaking process here wipes clean the brothers’ slate, allowing two bruised and battered celebrity siblings to find companionship once again.

The Plan that Came from the Bottom Up

Steve Sprung, Portugal/UK

Facing the decline of industry and the loss of their manufacturing jobs at Lucas Aerospace in 1976, a group of workers came up with ‘The Lucas Plan’. It was an attempt to use their skills and the equipment of the factories to steer the company’s output away from arms and towards useful, sustainable products, with wind turbines and hybrid cars among their forward-thinking ideas. Neither their bosses nor the government would accept their proposals, and so the workmen’s hopes for change and alternative successes were quickly lost. An opportunity for a positive shift in production, with employees at the heart of the movement, was ignored in favour of seeking maximum financial gain for a select few.

Described as “a film letter in parts”, The Plan that Came from the Bottom Up is a lengthy yet thorough depiction of the injustices of Britain in the 1970s and the lasting repercussions felt to this day, from nationwide unemployment and the loss of blue-collar work to environmental issues and climate change. The workers at the Lucas factory are defiant and passionately angry in the film, and in being confronted with truly threatening circumstances, took their own vulnerability and attempting to turn it into creativity and achievement. Director Steve Sprung weaves together new interviews and old footage to present an important critique of profit-hungry capitalist politics, to lament the lessons that have not been learnt, and project a hopeful vision for the future.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.