Web exclusive

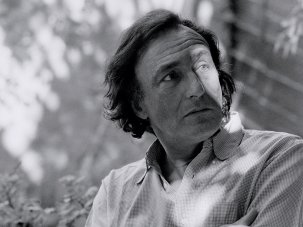

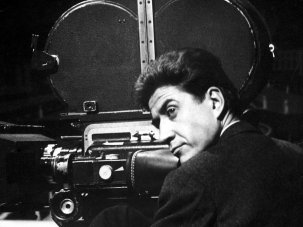

Chris Marker knocked at the door of my home in Santiago de Chile in May 1972. When I opened it I bumped into a very slim man who spoke Spanish with a Martian accent.

“I am Chris Marker,” he said.

I moved back a few centimetres and stood there looking at him in silence. Through my head went some of the images of his film La Jetée, which I had seen at least 15 times.

We shook hands and I said: “Come on in.”

Chris Marker entered the living room and waited until I invited him to sit down. He did not say anything. But I intuited from his weary gaze that he had not left the spacecraft in which he had landed properly parked.

From the first moment, Chris projected an alien image that never left him. He separated sentences with unexpected silences and spoke with a slight lisp, pressing his thin lips together, as if all earthly languages were foreign to him. He seemed very tall, although he wasn’t particularly. He dressed in an indescribable way. He was like an elegant worker. His face was long and thin, his eyes slightly oriental, his head shaved, and his ears like those of Doctor Spock.

“I liked your film,” he told me.

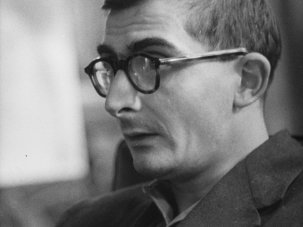

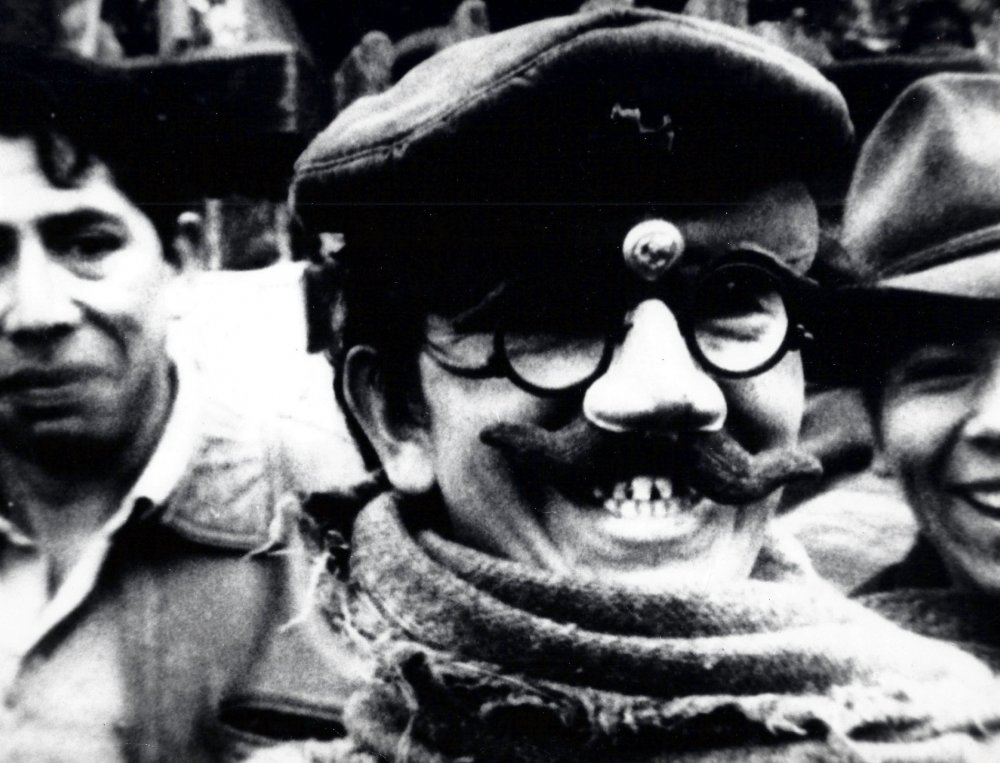

I was overwhelmed with a feeling of terror, a mixture of insecurity and respect. Not so long before I had finished El primer año (The First Year) – my first feature documentary, about the first 12 months of Salvador Allende’s government.

“I came to Chile with the intention of filming a cinematographic chronicle,” Marker confessed. “Since you’ve already made it, I’d rather buy it from you and exhibit it in France.”

It’s been 40 years since that conversation, and it’s only recently that I realised that it marked my life forever, since my modest amateur career in film made an enormous U-turn from that very moment. In his suitcases Chris Marker took away with him a 16mm negative of the film, as well as the perforated magnetic tape for the soundtrack.

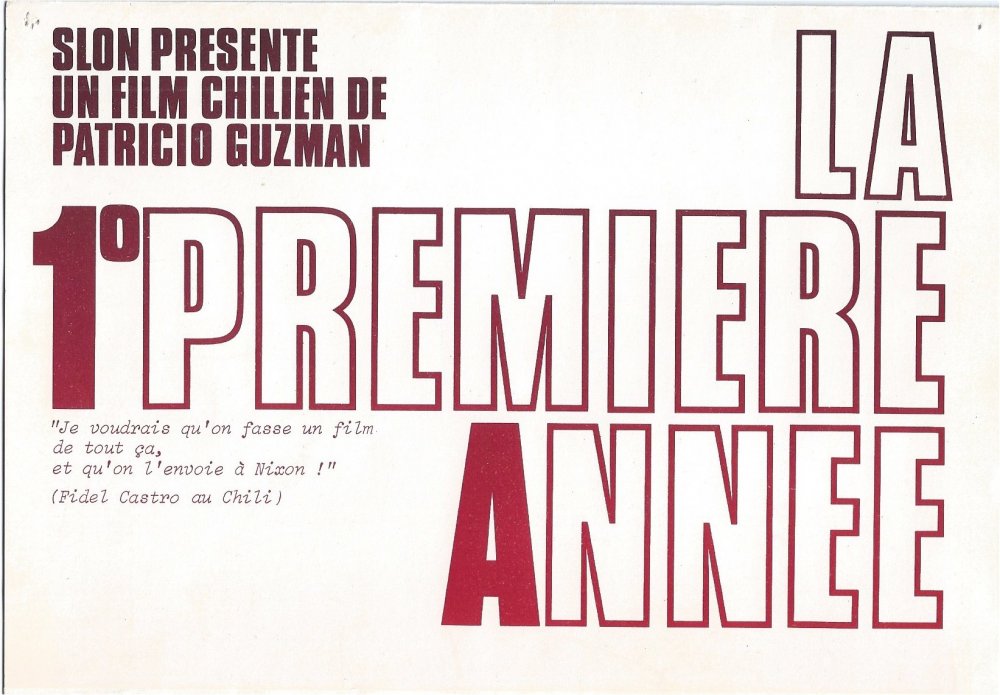

Months later he sent me the promotional material for The First Year, and wrote to me describing in detail the film’s premiere at the Studio De La Harpe in Paris. I received a review published in the magazine Le Temps Modernes (founded by Sartre), whose editor was Claude Lanzmann. Chris Marker not only wrote a positive review of the film, but also directed the exceptional dubbing for it. First he asked for my permission to tighten up the film (it was 110 minutes long). Of course I agreed. The truth is that the film was a little bit reiterative. I was never happy with the editing. It had some moving scenes. But there was no doubt it could lose ten minutes, even more.

He also made an introduction (approximately 8 minutes long) where he outlined the history of Chile in just a few words, in particular the history of the workers’ movement headed by Allende. It was a montage of black and white stills that Raymond Depardon had taken not long before in Chile. The narrative, written by Marker, was a wonder of synthesis. The music, based on atonal strings, was oneiric. This short film was attached to my film; when it concluded, the credits for The First Year started.

The film needed explanation, since a fair number of the audience knew nothing about Chile. There were worse problems, however. In 1972 the audience did not accept documentaries with subtitles. Therefore it had to be dubbed into French. Chris summoned all of his Parisian friends to dub the voices of the Chileans. They were high profile figures of the time: François Périer was the narrator, Delphine Seyrig a bourgeois woman, Françoise Arnoul and Florence Delay dubbed the workers. He even used the voice of the film’s distributor, Anatole Dauman (Argos Films), and brought in a famous draughtsman, Folon, to do the poster.

I couldn’t believe it.

This unexpected event produced in me a feeling of unreality. Something unimaginable was happening. Because The First Year was a modest 16mm film without synchronised sound, very low budget, with no greater ambition than showing the happiness of workers who toil with their hands – in fact all the workers and the miners during the first year of Allende – so the most we could have hoped for was distributing six copies on 35mm (which were struck in Alex in Buenos Aires), which would show for a couple of weeks in a few Chilean cinemas. Thanks to Chris, however, The First Year was shown in many cities, in countries such as France, Belgium and Switzerland; it won a prize at the Nantes Film Festival and got the FIPRESCI prize at Mannheim.

A year later (towards the end of 1972) my situation changed radically… The right managed to create a sense of chaos in the majority of Chilean cities thanks to those who opposed the Allende regime and financial assistance supplied by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. A mood of uncertainty gripped the country.

Furthermore, we had been sacked from the company Chile Films, where we were preparing a feature film. Eight months of work wasted! The company, like many others, could not survive the downing of tools organised by the right in October. Because of this brutal strike, the government banned the import of some products, amongst them film stock. That morning we were in the Forestal park with a team from The Battle for Chile pondering what to do about our situation. What to do!Whilst looking for a solution (almost impossible in practice), I thought of writing a letter to Chris Marker.

I still have that letter. I have selected the final paragraph for inclusion here:

As has happened at other times, I wasn’t able to reply to your letter immediately… Our political situation is confusing and the country is in a state of pre-civil war, which is causing a lot of tension… The bourgeoisie will deploy all its resources. It will deploy the bourgeois legal system. It will deploy its own professional organisations together with Nixon’s economic power…

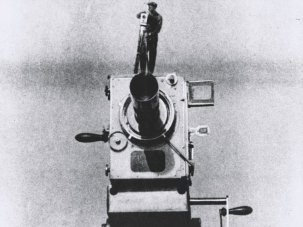

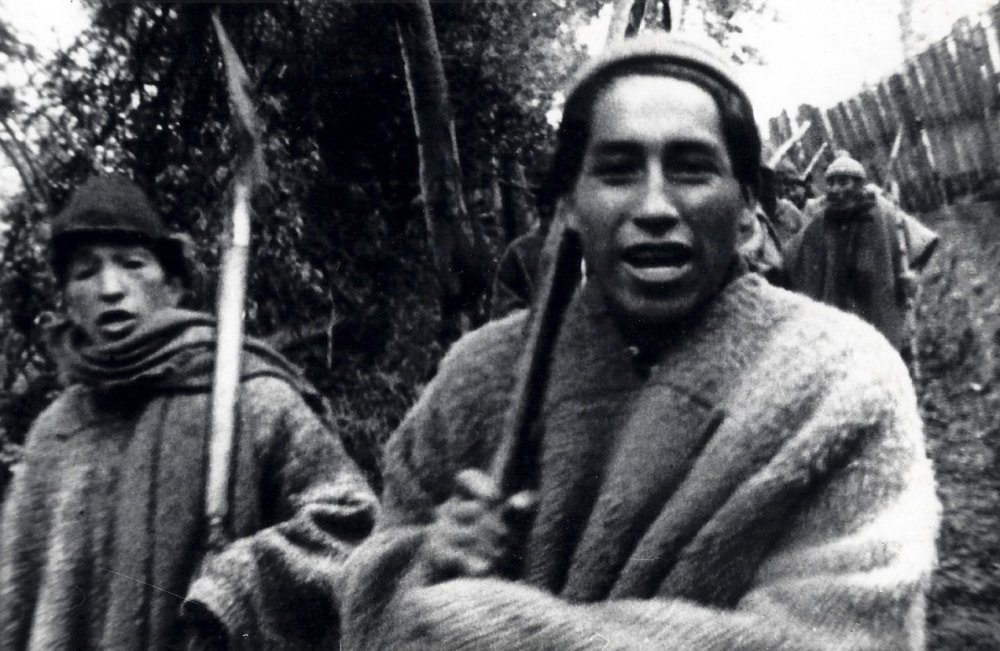

We must make a film about all this!… A wide-ranging piece shot in the factories, the fields, the mines. An investigative film whose grand sets are the cities, the villages, the coast, the desert. A film like a mural, split into chapters, whose protagonists are the people and their union leaders on the one hand, and the oligarchy, its leaders and their connexions with the government in Washington on the other. A film of analysis. A film about the masses and individuals. A fast-paced film vibrating with the energy of daily events, whose length is unforeseeable… A free-form film that draws on reportage, the essay, still photography, the dramatic structure of fiction, the sequence shot – that will use everything, depending on the circumstances, and the way reality proposes it…

However, WE DON’T HAVE film stock. Due to the US blockade on film imports it can take up to one year to get here. We thought you could help us get hold of the material… I am very sorry for the long letter, and, I ask you to please be absolutely frank in your reply. I completely trust your judgement.

Best wishes, Patricio.

Santiago de Chile, 14 November 1972.

A week later I got a telegram from Paris:

I’ll do what I can. Best wishes, Chris.

Approximately a month later a parcel arrived at Santiago Airport; a parcel that was sent directly from Kodak’s factory in Rochester, that was allowed in by customs because it did not incur any costs for the state. Chris Marker arranged it all in Europe and placed the order directly with the factory in the US. The box contained 43,000 feet (approximately 14 hours) of 16mm black-and-white film, plus more than 134 perforated magnetic tapes for a Nagra.

We had our second moment of glory thanks to Chris Marker.

The five members of the team on The Battle for Chile just couldn’t believe our eyes when we saw the glowing film canisters (they looked like mirrors). We had never seen new film canisters before, since we always worked with expired stock. It was also the first time we saw the cardboard boxes of the magnetic tapes. We had to start filming immediately, and with the utmost care (so we didn’t finish the stock too soon).

We developed a plan of the conflict areas, drawn on one of the walls of our office. It was a ‘theoretical map’ that took up half of our time. It was written with black markers on white card sheets. It outlined the economic, political and ideological problems. Each of them opened onto a second layer: control of production, control of distribution, relations of production, the ideological struggle with regards to information, the approach to battle… Doubtless, this plan must have provoked more than one smile in Chris. In his next letter he made me see that it was impossible to film so many things. However, what Chris didn’t know is that this ambitious ‘theorisation’ was made with just one objective in mind: to avoid using the film stock too quickly and wasting it, so we wouldn’t look bad in his eyes.

After the coup, and after being imprisoned for two weeks in Chile’s National Stadium, finally I was able to fly to France. It was an exciting moment. The ticket was paid for by my old Spanish colleagues from the Madrid Film School. At Orly Airport, Chris was waiting in a room, almost completely on his own. He looked at me with curiosity; he used his hands to shade his eyes, he shifted position. He could not recognise me because I had shaved off my beard.

We drove to Paris in a new car. We arrived at a luxurious house where we had lunch. The atmosphere was elegant. There were beautiful women (maybe from the film world); Chris was a great seducer. But he was undoubtedly the most important Martian in the meeting. My French was dreadful. For years I could hardly ever understand what was being said. My ability to simulate comprehension became almost perfect. After the lunch we went to return the car (it was borrowed). Finally, we took the metro, dragging my suitcases. We eventually arrived at a cheap hotel. We said goodbye and Chris drove off on a second-hand motorbike (that was his own).

We started out on a long pilgrimage to raise money. We had dinner at Fréderic Rossif’s house together with Simone Signoret. We had dinner at the house of actress Florence Delay. We spoke with dozens of personalities in order to be able to edit and finish The Battle of Chile. We had several meetings with Saul Yelin, a brilliant diplomat from the ICAIC, to tell him about our aims. Several months passed by. I lived for many weeks in the house of another female friend of Chris’s, in Saint Sulpice.

Finally, Alfredo Guevara, president of the ICAIC, approved the project from Havana and we were able to travel to Cuba to finish The Battle of Chile. Chris had had for a long time an excellent relationship with the Cubans, which doubtless came about because of two documentaries he shot on the island: ¡Cuba Sí! and La bataille des dix millions. I was lucky to be able to capitalise on this good relationship and go to Havana. It was a crucial moment, because after 1974 relations between Chris and the Cubans suddenly turned cold, after the premiere of A Grin without a Cat (Le Fond de l’air est rouge), in which Chris criticises the regime.

I moved to Cuba supposedly for six months and ended up living in Havana for six years – the time it took to edit The Battle of Chile with Pedro Chaskel. I went back to Paris for the first time in 1975 to premiere the first part of the film, which was selected for Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes in 1975. Federico Elton (the film’s production manager) and I dropped by to leave a copy of the film in the offices of SLON, the cooperative founded by Chris (previously known as ISKRA).

The next year Federico Elton and I repeated the same operation: we premiered the second part of The Battle of Chile in Directors’ Fortnight in 1976 and at the same time we left a copy at SLON for the attention of Chris…. But we never got an answer. We never received a note, a letter, a message, not even a phone call about the film from him. For months we kept asking ourselves “Why hasn’t he replied?” For years now I’ve asked myself the same question.

It has to be said that we were living in very politicised times, and the group that Chris belonged to was comprised of artists and intellectuals from the very radical left. My film wasn’t. On the contrary, The Battle of Chile is pluralist and not dedicated to any particular militant group; only to the Chilean dream (the struggle of an unarmed people), the utopia of a people in its broadest perspective, which I could see with my eyes and feel with my body in that vibrant Chile with which I identified, and still identify today.

Indeed, for a long time I felt it was difficult for me to gain recognition in France for my work of direct cinema, the first of its kind in Chile, and one of the few in the world that shows step by step the agony of a revolutionary people. Aside from the famous critic Louis Marcorelles, nobody got to the bottom of my film. Marcorelles understood my search as an artist, the novelty of my way of filmmaking, the historical impact of my work; his wise reviews in Le Monde accompanied the premieres of the two first parts in Cannes. Apart from him, there was at that time a great silence on the part of my French colleagues, and for a long time after. Meanwhile, The Battle of Chile went around the world.

I never bumped into Chris again, and was never in direct contact with him either during the last few decades, apart from a nice encounter at the San Francisco Film Festival in 1993. For the last 12 years we lived in the same city and I followed his work very closely. It has to be said that he always lived a very secluded life and was shrouded in a certain mystery.

At this moment, in the cemetery at Père Lachaise, showered in the tributes that your closest will pay you, I have just one final thing to say to you:

GOODBYE MY GREAT FRIEND, BON VOYAGE, THANK YOU FROM THE BOTTOM OF MY HEART FOR ALL THAT YOU HAVE GIVEN ME. It’s the best thing that’s happened in my life. WE SHALL OVERCOME!

—PG. París 2 August 2012.

Translated by Mar Diestro-Dópido.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.