Web exclusive

The Act of Killing

In an age when every self-respecting liberal burg in America, from Mill Valley to Montpelier, has a little film fest, it’s easy to forget that Telluride – which will toast its 40th birthday next year – was the first. A celebration-of-cinema born of the Berkeley counter-culture, whose co-founder, Tom Luddy, forged his sensibility in the midst of the Free Speech Movement whilst feasting on his friend Alice Waters’ boullabaise, this is a festival that earns its repute as a haven for cineastes.

Telluride Film Festival

Colorado, USA | September 2012

The vibe is much less Harvey Weinstein than Werner Herzog (a faithful attendee). For first-time directors, the business done here is less about selling your work than discussing its merits and failings with your artist-heroes, and finding collaborators for your next.

Driving to this remote site from Albuquerque or Denver, one winds around vertiginous switchbacks toward a high box-canyon in the southern Rockies. You can’t help but think that part of why Telluride is now far less known than its most famous imitator – Sundance – is that it’s damn hard to get to. What keeps the pretenders and paparazzi away, though, surely contributes to the rare air of a festival whose cineaste rep is enhanced, each year, by a guest director invited to curate a side-program of films near their hearts.

Last year, the great Brazilian singer-cum-cinephile Caetano Veloso presented classics by Godard and Glauber Rocha, and recalled how another of his selections, Rene Clair’s little-known Le Grandes Manoeuvres, re-oriented his life when it passed through his rural Bahian hometown in 1955.

This year, the British writer Geoff Dyer presented a programme highlighted by the subject of his latest book – Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, screened here in a rare 35mm print – and recounted how Tarkovsky, during his own pilgrimage to Telluride in the early 80s, had rolled through nearby Monument Valley and exclaimed to Tom Luddy that only Americans could be so vulgar and materialistic as to make cowboy movies in a landscape only suited to meditations on God.

Midnight’s Children

In recent years, Telluride’s official show of 25 exactingly curated films has included a wealth of Oscar-winners: among the recent sleeper-hits to premier here are The Artist, The King’s Speech and Slumdog Millionaire. Whether or not this year’s crop of prize-worthy previews – Roger Michell’s Bill Murray-as-Franklin Roosevelt vehicle Hyde Park on the Hudson; Sarah Polley’s affecting meditation on family and self The Stories We Tell; Michael Winterbottom’s fruitful experiment in capturing time’s passage in film Everyday – will find similar plaudits is anyone’s guess.

But the programmers also served their patrons well, this year as ever, by bringing ballyhooed award-winners from the big European festivals before American eyes for the first time – Christian Petzold’s Silver Bear-winning drama at Berlin Barbara; Michael Haneke’s Ballon-d’Or-garnering ode to the wages of mortality and love Amour (Love); and, also from Cannes (and likewise in the London Film Festival), Pablo Larraín’s assured, intelligent treatment of the Chilean campaign to reject Augusto Pinochet’s rule in 1988, No, carried by the ever-intelligent Gael García Bernal.

Alongside larger-scale Hollywood fare like Ben Affleck’s well-received CIA drama Argo, the pick of small-scale productions on show here was Haifaa Mansour’s Wadjda, an intimate story about a young Saudi girl’s dream to own her own bicycle – and the first feature ever shot by a woman in Mansour’s homeland.

In what was a bumper year for women directors here, this year’s program also included Sally Potter’s shimmering portrait of teen friendship in the age of the Cuban missile crisis Ginger and Rosa, and Deepa Mehta’s kinetic adaptation of Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie’s Booker-of-Booker-winning novel about the birth of India and Pakistan. Shot with all the verve we’ve come to expect from the ambitious maker of Fire and Water, Mehta’s film was warmly by Telluride’s crowds, but its kaleidoscope of images may require another shake-out in the editing suite to gain the narrative clarity needed to connect with a larger audience.

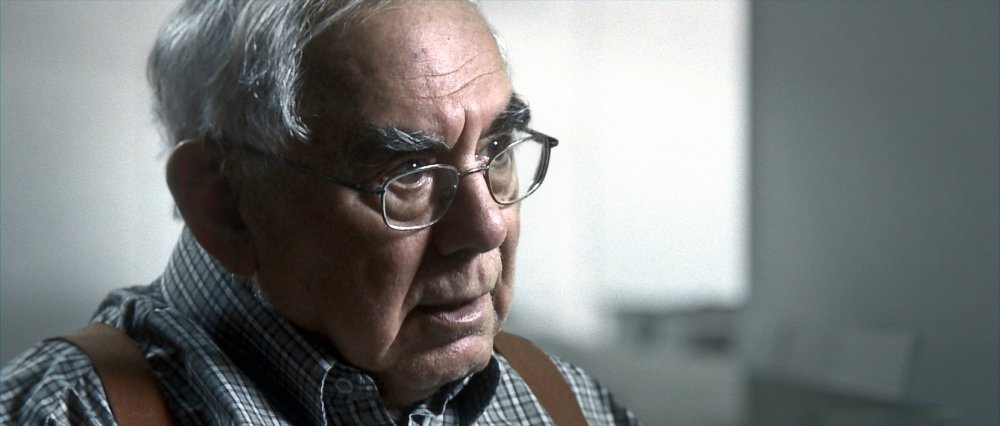

Another new work to ignite much dinner-table buzz here was The Gatekeepers. Borrowing from the template of Errol Morris’s The Fog of War, Dror Moreh’s potent documentary stitches together on-screen interviews with the last six leaders of Israel’s Shin Bet – the feared security agency chiefly responsible for protecting the Jewish homeland, by any means necessary, since 1968. By somehow convincing these spymasters to sit for his camera (their agency’s name means “The Defender that shall not be seen”), Moreh has forged an unprecedented look inside Israel’s approach to policing the Palestinian inhabitants of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Lending unassailable credence to oft-dismissed progressive Israelis’ critiques of the strategic – and moral – consequence of Occupation, Moreh’s searching film also amounts to a devastating account of how the modern Jewish state, as one of its avuncular stars proclaims, has arrived at a future where “it is winning every battle, but losing the war.”

The Gatekeepers

This wasn’t a crop of films put off by weighty themes. And The Gatekeepers aside, no treatment of those topics prompted more strong reactions than another documentary (or was it?) to which Errol Morris himself had recently attached his name as executive producer. Hard to imagine a better plug than that – until you read Werner Herzog’s view “I have not come across a documentary as powerful, surreal, and frightening in a decade.” The Act of Killing, by first-time director Joshua Oppenheimer – who began his career at Telluride’s student film lab – did not disappoint.

Excavating an all-but-forgotten episode in the shadow history of the Cold War once waged by Robert McNamara and co., The Act of Killing begins by recounting how, in 1965, Indonesia’s US-backed dictatorship enlisted death squads to kill off upwards of a million alleged leftists and sympathisers.

The premise is familiar. But that’s where any similarity with documentary convention ends. Foregoing the use of archival footage, or interviews with victims or experts, the event’s of modern Indonesia’s primal tragedy are recalled here through an unsettling source: the memories of its perpetrators – many of whom have not only never been punished for their crimes, but today live as prominent citizens fêted on TV for cleansing Sumatra of Soviet plots. Oppenheimer and his co-directors turn their cameras on these dark figures, asking them to create scenes re-enacting their harrowing deeds.

The result is a film at once wrenching and bizarre: a sequence of colour-drenched tableaus adding up to what must be one of the most complexly fine reckonings with the evil men do – and the stories we tell ourselves, in order to live – as we have.

Not everyone at Telluride agreed. Some attendees at the screening I saw walked out; Geoff Dyer, when I interviewed him, made plain his repulsion. But love or loath this patently disturbing film, it was hard not to feel that it had prompted a kind of conversation with which this site for cinematic pilgrimage has grown accustomed: about how this film, as Dyer says of Tarkosky’s Stalker, might too “expand our sense of what a film is, and what it can do.”