This is an extended version of an interview from our August 2012 issue

“The perfect story is one you can retell in three minutes, and every single sentence is interesting,” advises Malik Bendjelloul. “When I told people the skeleton of this story, it was like ‘Wow!’ and then ‘wow!’ and then ‘wow!’… I’d never heard a story that provoked so much energy when I told it.”

Searching for Sugar Man is released on 26 July 2012.

Bendjelloul’s story, expertly unfolded in his feature-documentary debut Searching for Sugar Man, produced by Simon Chinn (Man on Wire), is one of faraway times and disparate cities, of missed chances, unlikely cross-cultural pollination and the stirring satisfactions of belated recognition.

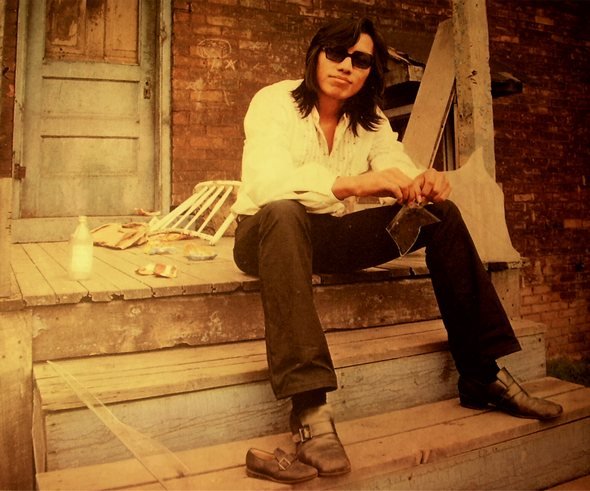

It’s also one whose pleasures of revelation are hard for a journalist not to spoil (you can read a fuller synopsis in Sam Davies’ review in our August 2012 issue), but it starts like this: despite the attentions of producing legends Mike Theodore and Steve Rowland, the two albums recorded by enigmatic inner-Detroit folk-rocker and wandering spirit Sixto Rodriguez in 1970 and 1971 (Cold Fact and Coming from Reality) confounded all expectations by sinking without trace, and in a weird realisation of the lyrics of his last recorded song, his label laid him off two weeks before Christmas.

Somehow, though, the records washed up in apartheid-era South Africa, where their fresh and frank protest lyrics struck a chord with a younger liberal generation suffocating under the repressively conservative regime; we’re told Cold Fact even introduced the word “anti-establishment” to the country. Slowly Cold Fact became, to South Africans, “one of the most famous records of all time”, “bigger than Elvis”… “Oh, much bigger than the Rolling Stones.”

Still, it wasn’t until the mid 90s that anyone there seriously investigated the artist’s curiously divergent record-cover credits, or the conflicting myths of his post-recording denouement (“It wasn’t just a suicide – it was one of the most grotesque suicides in rock history”), or the money trail of this covert multi-platinum seller…

Stephen Segerman

Bendjelloul was travelling the southern hemisphere looking for short stories for Swedish TV when he met Stephen ‘Sugar’ Segerman, a Cape Town record-shop owner who regaled him with the full tale.

“I thought, ‘this is the best story I ever heard in my life,’” Bendjelloul says. “Why had no South African director already told it? That’s the big strange thing. But to be honest I think in South Africa this story’s too famous – it’s like making a documentary about the Rolling Stones; why do that when everyone already knows it? In a way it was important that I was someone from the outside who experienced it like new.”

I complement him on the film’s careful series of reveals. “But it’s not contrived,” he emphasises. “My hiding the facts – this is chronologically how it happened.”

I tell him I’m reminded of the Buena Vista Social Club phenomenon – another cultural petri-dish story of music developing in isolation.

“Correct, very much so. It can’t happen today, and this case was very extreme,” says Bendjelloul, counting off three factors: one, a hermetic country censored from the inside and boycotted from without; two, “this isolated man”, Rodriguez himself, who for long periods could only be contacted through the telephone at his local bar; and three, the wideness of the world before the internet. “And all these things were resolved after apartheid fell in 1994, and the internet came at the same time.”

Malik Bendjelloul

And the mystery man himself, who as a construction worker apparently used to turn up to work in a tuxedo? The film ends with some beautiful testimony from Rick, an old bricklayer colleague of Rodriguez, who compares him to “a silkworm, taking his life and spinning it into something beautiful, transformative, perhaps transcendent.”

“I think it’s true,” says Bendjelloul. “Rodriguez tells something about this world: every day can be a special day; construction work is maybe the most important work there is, if you just look at it that way. It’s just a way of perceiving things and believing what you do with your life has an importance. Rodriguez proves that: he wrote some songs at his kitchen table and changed the world without even knowing it, and created art that maybe will be around forever.”

-

Sight & Sound: the August 2012 issue

The genius of Alfred Hitchcock: Guillermo del Toro on the Master of Suspense; plus Christopher Nolan, Patricio Guzmán, Bruce Lacey, Boris Barnet,...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.