Web exclusive

Just as it’s impossible to imagine the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone without the Ennio Morricone scores that accompany them, the James Bond movies of the 1960s and 1970s might never have become such a phenomenon without the music of John Barry. His scores on a dozen Bond movies – from Dr No (1962), on which he worked uncredited, to The Living Daylights (1987) – have a sense of romance, mystery, pizzazz and sheer majestic scale that the rather mechanical films themselves often struggle to match.

Born John Barry Prendergast in York in 1933, Barry came to prominence in the Swinging 60s, when as a hip young songwriter, arranger, trumpeter and bandleader (married at the time to Jane Birkin) he was able to take advantage of the influx of big Hollywood productions to London. An uncredited last-minute salvage job on the score for Dr No (officially credited to Monty Norman) led to an offer of work on the next instalment, From Russia with Love (1963), while the following year his rousing score for Zulu demonstrated his versatility.

Barry had taught himself composition during his national service in Cyprus, via correspondence course with Bill Russo, a legendary arranger for the Stan Kenton big band. Russo’s brass ‘wall of sound’ left its mark in Barry’s score for his next Bond film, Goldfinger, and Barry went on to write jazz-inflected scores for such documents of 60s London as The Ipcress File (once again for Bond producer Harry Saltzman) and The Knack… and How to Get It (both 1965).

But Barry’s first love had always been classical music, not jazz – as he revealed on Desert Island Discs in 1999, on which he stuck strictly to the classics, picking symphonic works by Stravinsky, Beethoven, Dvorak Mahler, Shostakovich, Bruckner, Sibelius and Rachmaninov. Though he returned occasionally to jazz in later years (his haunting clarinet and piano score for Wim Wenders’s 1982 Hammett remained a personal favourite), as his star rose he became equally well known for lush, achingly melodic orchestral scores conjuring up great yearning romantic vistas. Born Free (1966) won him two Oscars for Best Song and Best Score; three more followed, for the Carmina Burana-influenced medievalism of The Lion in Winter (1968), Out of Africa (1985) – perhaps the quintessential Barry score – and Dances with Wolves (1990).

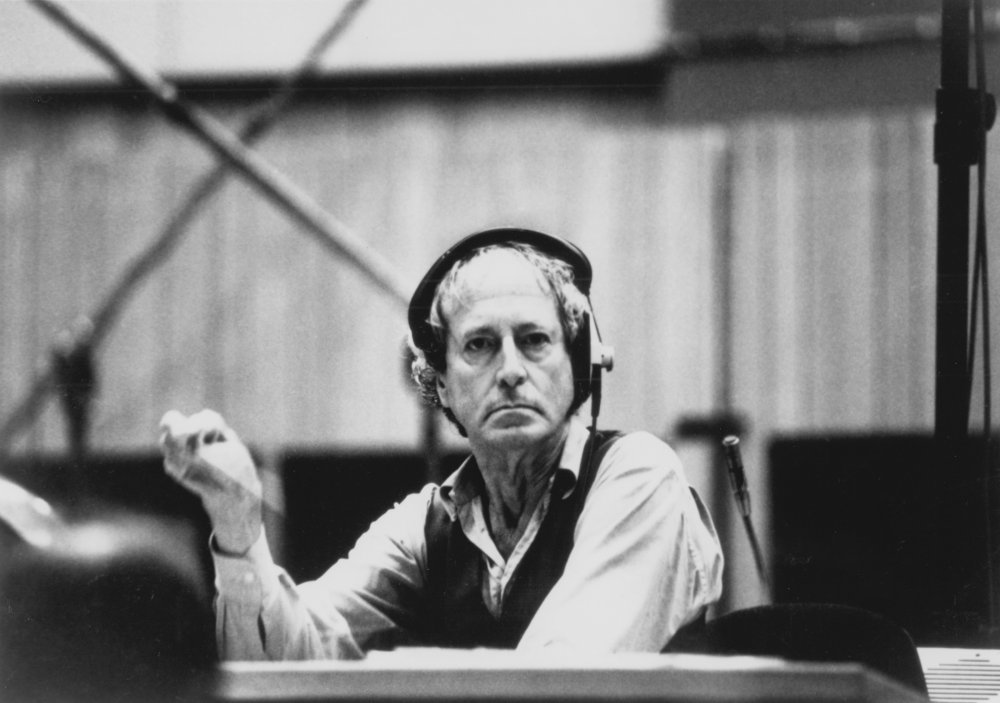

Though he dabbled with synthesisers on the theme tune for the 1971 TV series The Persuaders and later on his only electronic film score, Jagged Edge (1985) – and went on to collaborate with Duran Duran and A-ha on 1980s Bond theme songs – Barry remained committed to orchestral recording throughout his career. When I interviewed him in 1998 – while he was promoting a rare non-soundtrack release, The Beyondness of Things – Barry said he couldn’t understand the younger generation of film composers who didn’t conduct their own work: “If you do synthesised stuff, it’s all to click tracks, but if you have an orchestra and you’re conducting your own music, you can push and you can pull. There’s a whole other life to the music that you have with an orchestra. You can take one bit a little faster, then slow it down, start to dance with the whole thing.”

Though he’d lived in the US from 1974, Barry kept a pied à terre in Chelsea’s Cadogan Square, round the corner from his 1960s stamping ground, and never lost his gravelly Yorkshire accent. He had a dry Yorkshire sense of humour too, professing himself baffled with the enduring singing career enjoyed by his ex-wife Jane Birkin in France: “I thought she could have had a much bigger career as an actress,” he told me. “The singing never came up when we were together. I didn’t know she had any talent for singing. And then I did a musical with her [1965’s Passion Flower Hotel] – and realised she didn’t have a talent for singing.”