Web exclusive

Elephant

If you believe, as I do, that the golden age of what used to be called ‘world cinema’ (in imitation of ‘world music’) was during the 1990s, then you can further that claim to say that ‘world cinema’ had its biggest impact on American cinema – just as French New Wave cinema had done in the 1970s – just after the turn of this century.

For instance, in his two radical leaps Gerry (2002) and Elephant (2003), Gus Van Sant seemed to have absorbed the more unblinking contemplative approach to filmmaking of Béla Tarr (amongst others) in reaction to the fast-cutting, multiple-viewpoint method of mainstream Hollywood fare (what David Bordwell has called “intensified continuity”). But the element of Van Sant’s twin breakthrough films that gave that new approach its American aesthetic enhancement was Harris Savides’s cinematography.

Savides, who has died (of brain cancer) tragically young at 55, was a graduate of the School of Visual Arts in New York who began as a fashion photographer. He gained his first DP credits in 1993 on the TV movie Lake Consequence, and on Cindy Crawford: The Next Challenge Workout. His first movie feature was Phil Joanou’s Alec Baldwin vehicle Heaven’s Prisoners (1996), but it was his dazzling opening credits for David Fincher’s Se7en (1994) and the immense subtlety and finish of the lighting in Fincher’s The Game (1997) and James Gray’s The Yards (1999) that saw him rise to the top rank of DPs.

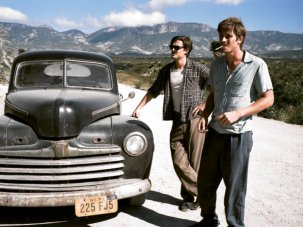

Gerry

Three regular collaborations mark his career: six features with Van Sant, three with David Fincher, and a clutch of music videos with Mark Romanek (such as Michael Jackson’s Scream and Madonna’s Rain). His work with Van Sant began on Finding Forrester (2000), a lachrymose boy-meets-mentor film widely regarded as a rare Van Sant mistake, but it was a happy coming together none the less because the sequence of movies that follows from Gerry through Elephant, Jonathan Glazer’s Birth (2003), Van Sant’s Last Days (2004) to Fincher’s Zodiac (2005) must be one of the most era-defining in recent cinematographic history.

The complex choreography of the chilling Steadicam takes at the school in Elephant is one thing, the mesmerising profile shots of the boys tramping through the desert in Gerry is another, the skin-pricking eeriness of the faces and apartments in the under-rated Birth yet another; but what makes almost every Savides shot so eloquent is that he always allows the quality of the locale, space or scene to play itself and not be subdued.

Savides has said he worked “in the service of keeping it natural and simple and not over-glamorising it.” One thinks of the way the gorgeous light plays around the couple at the lakeside when they encounter the killer in Zodiac, not knowing they’re doomed. If Savides had a mantra, it was, perhaps, “you don’t want to get to a point where the audience notices the light.”

Zodiac

If there was a hallmark, it was something of an ‘end-of-days’ quality to many of his shots, the poetry of a bewildered vestigial cool that particularly marks Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere (2009). I’d say it’s likely that most of these Savides-shot films will be seen as American classics in the future.

So well loved and admired was Savides that there is already a wealth of tributes to his work to be found online, and for a quick sample of his mastery of light, framing and form, let me commend that at Slate.com.

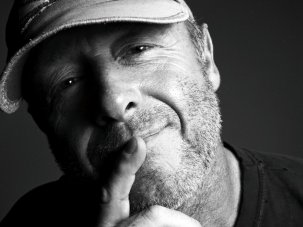

Harris Savides shooting Somewhere with Sophia Coppola

Postscript

DP Seamus Mcgarvey (We Need to Talk About Kevin, Avengers Assemble) writes:

Harris Savides was the most gifted cinematographer of his generation. His legacy of so many startlingly photographed films will never be forgotten. From the experimental verve of his music videos and commercials to the philosophical profundity yet deft simplicity of his feature work, Harris was the most sought after cinematographer, and directors and crews loved and respected him.

He was a virtuoso in that delicate dance between the lens and the light and was incredibly daring when it came to hovering on the edge of darkness… a precipitous place for any cinematographer! He used light in such an expressive way and he really understood how to look at an actor’s face with his camera in a way that allowed you to get under their skin. His was a rare and singular vision and he imbued each and every frame with his unique artist’s eye.

The genuine sadness and tragedy of Harris Savides’ early passing is only tempered by the fact that he has left us a rich and inspirational series of works which will forever urge filmmakers to explore their creative imaginations and push the limits of this fast-evolving art form, Cinema.