Festival blog | Web exclusive

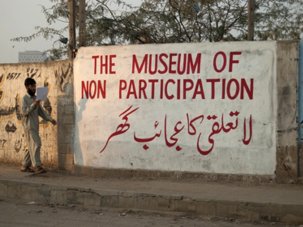

Nitsch

- LUX/ICA Biennial of Moving Images

24-27 May 2012 | London, UK

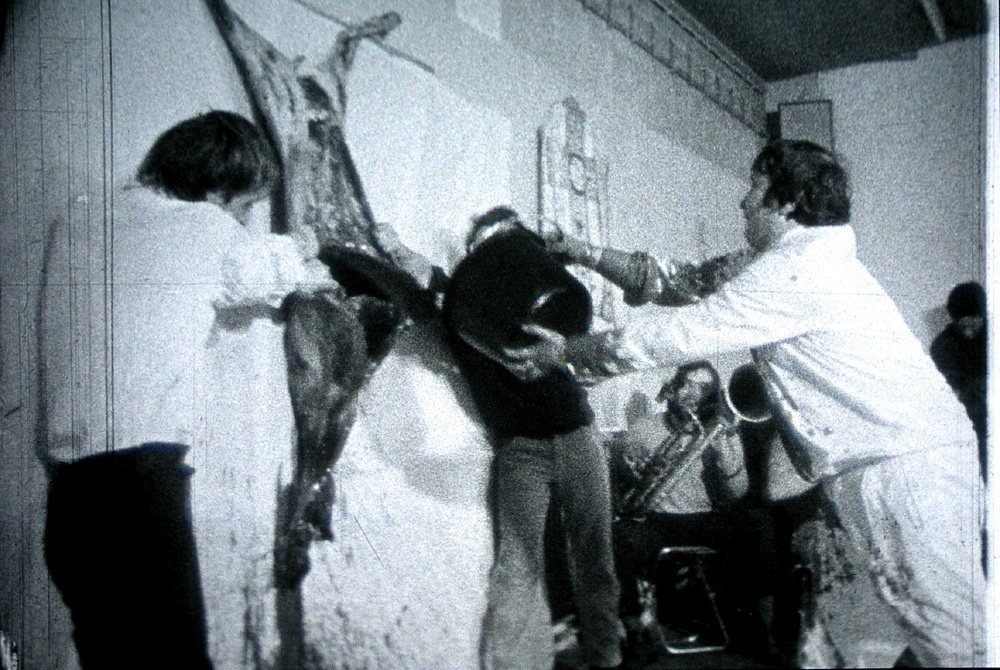

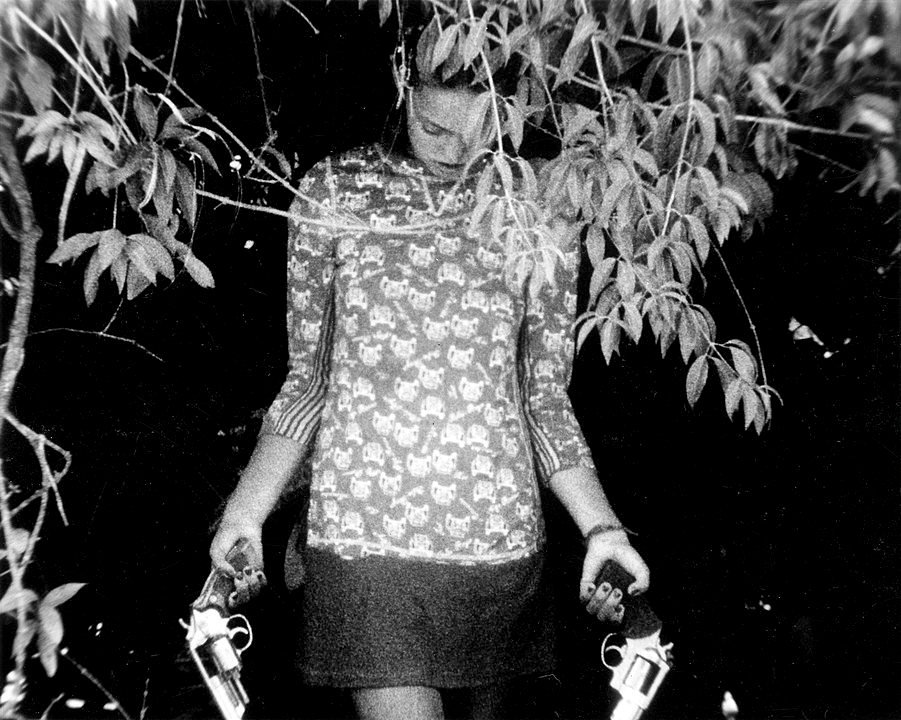

Here is a man rubbing animal innards into the genitals of a woman. It is 1969, and the Vienna Actionists are going at it in Irm and Ed Sommer’s Nitsch. Welcome to the first LUX/ICA Biennial of Moving Images.

We are sat on the floor in the ICA theatre and the screen is ablaze with rhythmic animation in Tony and Beverly Conrad’s Straight and Narrow, reprogramming our eyes something sublime; it is 1970. Mark Webber, programmer of the London Film Festival’s Experimenta strand and part-time pop star, spins some records.

Back from the bar and we’ve leapt to 1978, where a drunk woman is leering at us in Manuel De Landa’s anarchic dance of screen space, Incontinence: A Diarrhetic Flow of Mismatches, as the camera chops and swoops violently around impossible interior architecture.

While it would be overstating the case to suggest that this opening 16mm trio are meant as a declaration of intent for the festival to unfurl, they do throw down a good set of coordinates for the tropes displayed over the successive three days: politically charged work, performance, structuralist and abstract filmmaking, occasional bursts of comedy and regular disruption of narrative modes. In the absence of programme notes or live introductions, they also warm us to the common sensations of confusion, frustration – and joy – inherent in experimental-movie viewing. We are all alone in the dark and will have to work it out for ourselves.

Next we watch Roberto Rosellini’s 1958 feature The Machine That Kills Bad People. Why, we are never told; presumably because Webber likes it and this is a rare print. So why not?

Because really it is 1997, and we are back in the realm of his old ICA underground film/disco hybrid Little Stabs of Happiness, reincarnated for one night to launch the Biennial. And again, this pinging around in time is a good precedent for an event that frequently inspired the question ‘When are we?’

Straight and Narrow

Why a biennial of moving image in 2012, no-one asks. They built it and we came. But what are the walls made of and how will we find our way round? The elegantly designed festival brochure/catalogue – A5, red and white, 66 pages, serif font – at first gives little away (Ben Rivers once said that he would only travel to festivals whose brochures were matte-printed, and for me this has proven a good rule of thumb), with some brief introductions that are vague and gracious, but non-committal on the artistic direction of the programme. But soon it becomes clear that this is not a festival of films so much as a biennial of moving-image curators.

The schedule simply lists programmes as ‘Screening curated by…’, which admittedly may result from the spatial constraints of such programme titles as ‘WE ONLY DREAM OF PLACES AND RESISTANCE, FOR NOW’ or ‘THIS OBSCURE OBJECT OF DESIRE, OR, “NO IDEAS EXCEPT IN THINGS”’ – but has an instantly distancing effect on anyone not personally acquainted with their prior programming work. And while some provide thoughtful essays on the reasoning of their selections, it’s the curators’ own biographies which are given printing space under their programmes.

The Machine That Kills Bad People

This handing-over of responsibility for the selection of films could be seen as a democratic – or at least dispersed – programming tactic, and is worth investigating in the context of other events in the UK. In the North East, AV Festival has slowly (and elegantly) claimed the film/art/sound biennial crown, with its themed programmes selected and stewed over for 18 months, from the exploration of artists’ adventures in archives with a Recycled Film strand as part of their Energy edition in 2010 to their thorough and illuminating exploration of the Slow Cinema canon as part of As Slow As It Gets in 2012. For audiences at AV, the pleasure is the depth with which a timely aspect of moving-image culture can be delved into.

As the largest contemporary art event in the UK, the Liverpool Biennial is also themed, and like AV works with both centrally curated content and year-round partnerships with the programming staff at their partner venues. Themes are a little more amorphous (Made Up, 2008; Touched, 2010), and the art-forms range across the full spectrum of artists’ practices, but its place in championing exciting content cannot be underestimated. The introduction of Ryan Trecartin’s work to many UK audiences and press for the first time in 2010 is still a landmark, exposing the most exciting (and otherwise unnoticed) new voice in cinema.

While the LUX/ICA Biennial of Moving Images may be descended from the line of Aurora, the expanded festival of animation that ceased operation in Norwich in 1999, it is often reminiscent of Kill Your Timid Notion, the experimental film and performance festival based in Dundee, which offered a similarly mixed programme of old films with new. Tightly curated by organisers Arika, it was less themed than investigative, managing to be simultaneously hardcore in content and desirous of a genuine communication with its audiences.

So it is into this landscape that LIBMI (not a catchy acronym) steps up and flicks on the projectors, with its plethora of perspectives and concerns, and it is for audiences to build a picture connecting the dots. Which in the end is okay, because for the most part the curators are great and the films are amazing.

Peggy and Fred in Hell

Some highlights…

Rosa Barba’s curated programme ‘SUBCONSCIOUS SOCIETY’ opens magnificently with Leslie Thornton’s Peggy and Fred in Hell: The Prologue, a film that Thornton has been adding to and re-editing for over 25 years. Placing two children inside a world of disconnects – grinding machinery, tonsil photography, flashcards too quick for perception and a voice quiz designed for self-improvement on “the pitch most people prefer in a woman” – it’s a mélange of found footage with a slanted, occasionally magical, homemade sci-fi aesthetic. There’s undoubtedly a broader investigation of the effects of disparate pop-culture inputs on young minds, and indeed our own, involved at some level, but it’s hard not to become hypnotised when one child (of the future? In outer space?) sings ‘Billie Jean’ to the camera, all phonetic mishearings and half-remembrances.

The mood darkens with Jordan Lavi Quellman’s The Deteriorationists, where a couple destruct in reverse time, as we follow a violent elderly version to happier middle period and eventually their initial meeting. Some segments seem at first to be home movies, so authentically are they shot with period grain, the radio news placing us in the era of the Lewinsky scandal as the couple fight over whether peanut butter belongs in the fridge.

When reports emerged that the Chinese government had banned films about time travel, the reason suggested was a disrespect for history, but the potency of the strategy in The Deteriorationists, or François Ozon’s 5x2 – reverse-engineering a romantic implosion, looking for the seeds of discontent and the birth of dangerous power shifts – is how much the origins can sting (or as Feist sings in ‘Let It Die’, “The saddest part of a broken heart / Isn’t the ending so much as the start”).

Luther Price’s Meat

A much anticipated programme in the festival was the focus on Luther Price, an artist admired by Stan Brakhage and Carolee Schneemann. Price makes no copies of his hand-treated 16mm films, meaning that they rarely travel, but here he has entrusted them to curators Thomas Beard and Ed Halter of Light Industry in New York.

The camera-less films involve a spectrum of techniques for obfuscating and revealing pre-existing footage, including scratching, bleaching, re-editing and burying in the dirt for the emulsion to decay, and taken as a single programme they are intense viewing.

In Turbulent Blue we start with the blue-black colours streaked with neon sparks and flames of yellow that identify the action genre, except here the image has been bisected and the explosive climax is entirely devoid of sound. As a bald man traverses an industrial site, all guns blazing, a combination of split frames, double exposures and camera movements give the sensation that the reel is moving in many different directions at the same time. It would not be surprising if the projection booth itself exploded behind us. But silently.

Noisier works included Inkblot #1, which crackled and scraped with the optical soundtrack, white-on-black brushstrokes and bleach snow, the texture of the projection seeming to flicker between cream and bone. In The Mongrel Sister a melodrama about spiritual possession is chopped with footage of a snake, a tortoise and a toad, the latter providing a welcome earthy humour. Whilst these films exist to decay, there’s something lively about the intricacy and handiwork involved throughout, and as they rattle through the projector, menace intermingles with celebration in their celluloid death-drive.

Deep Westurn

Perhaps because Ben Rivers spent years as a cinema programmer for Brighton’s Cinematheque, his programme feels the most audience-friendly in tone and flow, themed around artists who collaborate.

We start in 1962 with Ron Rice’s Senseless, a kinetic free-association collection of images from Mexico and Venice Beach that hits us with broken glass, sweeps us into the path of a bearded pilgrim, and pauses amongst union activities, protests against unemployment and the arms race and finally more animal innards, as bull-fight spoils spurt for our sad delight, all to the swirl of dramatic Hollywood scores. Black-and-white and similar in energy to Ken Kesey’s Magic Trip footage, the adventure – spiritual, drug-fuelled, collective – is an infectious document of beatnik cinema, or what the upcoming On The Road adaptation should feel like but won’t.

Humour is found in several films in the programme, from the repetitive spectacle of four men falling off their chairs in unison in Robert Nelson’s Deep Westurn to the Monty Python-esque handbags at dawn of Stephen Sutcliffe’s The Garden of Proserpine and the ever-welcome bravado, sleaze and social unease of George Kuchar’s We, the Normal.

But a standout for this viewer is a film that hits an unusually seductive register, Laida Lertxundi’s Footnotes to a House of Love. A shack in the desert is the nexus for a group of beautiful people, caught in glimpses as they move through and around the building – the camera off to the side, or lingering in the space where an encounter (or nothing) may have occurred. It’s resolutely foxy stuff, bringing to mind the hair-in-the-breeze canyon filming of Ben Russell’s recent Trypps #7; and maybe there’s also something Malick-esque afoot, but with less Wonder and more stillness. All skin textures and ambiguous tensions, the film hits you something woozy, and offers a sense of cinema that many feature films would envy.

Footnotes to a House of Love

The multiplicity of programming voices means the festival journey becomes a more subjective and personal endeavour, its highlights found in moments of overlap or surprises, such as Jan Verwoert’s bravura lecture on the nature of failure, and curator Shanay Jhaveri reading a poem before his screening. Neither survey nor statement, the experience may be diffuse, but a Biennial’s legacy necessarily takes a while to manifest.

In a smart move, the Biennial commissioned several writers in residence to compile The Journal, a live blog that added commentary, interviews and reportage to the festival as it was happening, alongside a school for artists and a school for curating artists’ films. Alongside the strength of the films shown, these activities assured some impact of this event on the discourse, exhibition and production of new work, and this debut edition forged strong foundations to engage new audiences with the delights, disturbances and compelling nature of moving images.