Web exclusive

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Winter Sleep, this year’s Sight & Sound Gala

The Sight & Sound Gala

Winter Sleep

Screening Saturday 18, Sunday 19

Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Turkey 2014

With Haluk Bilginer, Melisa Sözen, Demet Akbağ

196 mins

UK distribution New Wave Films

We’re proud to announce that Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Winter Sleep is this year’s Sight & Sound gala film. The Turkish director deservedly won the Palme d’Or for this Chekhovian chamber drama, his seventh feature.

Ceylan’s previous, the existential crime saga Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011), introduced more dialogue into his predominantly visual, minimalist style of storytelling, and Winter Sleep continues this trend. Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), a retired actor and wealthy landowner, lives with his young wife (Melisa Sözen) and his divorced sister (Demet Akbag) in his boutique hotel in the rugged, snowy hinterland of Cappadocia (which Ceylan snatches through the hotel’s windows in the kind of desolately sublime shot that is his signature).

The film’s slow-burning drama evolves from an enigmatic incident at the start when a local boy shatters Aydin’s car window with a rock. It transpires that the boy is angry because Aydin has set debt-collectors on to his family for not paying their rent on time. The act unsettles Aydin’s relationships with his wife and sister and Ceylan observes the fallout through long, deftly scripted conversations that disintegrate into bouts of emotional warfare and self-reflection, given real intensity by some outstanding performances from Ceylan’s actors.

The wreckage of failed and failing relationships is strewn across Ceylan’s cinema, which has also never been shy of examining the cruel side of human nature. He has described filmmaking as “sending a letter to the darkness” and that’s certainly the case in this morally knotty and complex psychological study.

— Isabel Stevens

Other galas

Foxcatcher

Foxcatcher (2014)

Screening Thursday 16, Friday 17

Bennett Miller

USA 2014

With Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Vanessa Redgrave, Sienna Miller, Anthony Michael Hall

135 mins

UK distribution Entertainment One UK

For great bruisingly physical and psychological acting, you won’t find a more convincing trio than Steve Carell, Channing Tatum and Mark Ruffalo in Foxcatcher. Director Bennett Miller, of Moneyball fame, conceives of scene after scene of chilling humiliation in this tonally subtle true-life movie about John E. Du Pont (Carell), a super-rich sponsor who woos Olympic champion wrestler Mark Schultz (Tatum) to come to live and train at his Valley Forge estate. The relationship turns semi-abusive, with Behind the Candelabra overtones, as control-freak John draws in Mark’s more savvy brother Dave (Ruffalo) and eventually the whole USA wrestling team, with whom John insists on posing as a coach to impress his racehorse-devoted mother (Vanessa Redgrave). A film of persistent wintry mood in hues of blue and grey, its flaw is that it keeps beating us over the head with similar observations.

— Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

Mr. Turner

Mr. Turner

Screening Friday 10, Saturday 11

Mike Leigh

UK 2014

With Timothy Spall, Dorothy Atkinson, Marion Bailey, Paul Jesson, Lesley Manville

149 mins

UK distribution Entertainment One UK

Is there a director more suited to the task of bringing Turner’s life to the big screen than Mike Leigh – a filmmaker who deals in the quirks and dramas of ordinary folk and who has already proved with Topsy-Turvy, his delicious portrait of Gilbert and Sullivan, that he can breath fresh life into the biopic? Mr. Turner is, to quote Sullivan in Topsy-Turvy, no “trivial soufflé” but a tragi-comedy and an acute social critique. Unlike the thespian duo, however, Turner was an artist of humble origins who, through his patrons, was well-acquainted with high society, allowing Leigh even more opportunity here to delve deep into Victorian mores.

A jovial eccentric at times, surly and irritable at others, Leigh’s anti-heroic Turner has more of Naked’s Johnny in him than Topsy-Turvy’s Gilbert and Sullivan. “Don’t try to mask the dark side” was the advice Ruskin gave to Walter Thornbury when the journalist was embarking on the first biography of Turner in 1861 – words that Mike Leigh has certainly taken to heart.

— Isabel Stevens, from .

Whiplash

Whiplash (2014)

Screening Wednesday 15, Thursday 16, Saturday 18

Damien Chazelle

USA 2014

With Miles Teller, J K Simmons, Melissa Benoist

106 mins

UK distribution Sony Pictures Releasing International UK

In terms of pure exuberant pleasure, nothing touched Whiplash, the Sundance US Grand Jury prize-winner programmed in Directors’ Fortnight. Its plot, which focuses on Andrew Neyman (Miles Teller), a young man who wants to be a jazz drummer in the Buddy Rich mould, might sound like a recipe for tedium, but what makes it shimmer and thrill is the antagonistic relationship he’s forced into when he goes to a Juilliard-like conservatoire and meets the school’s jazz master Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons), a vicious martinet who seems to get off on humiliating young musicians. “That’s not my tempo. Are you rushing or are you dragging,” he yells at Neyman, whose hands are dripping blood. The film grew out of director Damien Chazelle’s short, but it’s so packed with tension it feels anything but extended or thin. The calibrated facility and fluidity with which Chazelle chooses shots and cuts (he also directed 2009’s Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench) surely heralds a rich directorial future.

— Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

The rest of the programme (in alphabetical order)

August Winds

August Winds (Ventos de Agosto, 2014)

Screening Saturday 11, Wednesday 15

Gabriel Mascaro

Brazil 2014

With Dandara de Morais, Geová Manoel dos Santos

77 mins

A dreamy, mysterious contemplation of death and the passing of time set in an isolated village on Brazil’s coast. Gabriel Mascaro seamlessly blends nonfiction observation of rural life and the natural world with quiet drama – the longing for escape of a city woman looking after her grandmother, her boyfriend’s obsession with a sea-swallowed corpse, a visiting meteorologist’s sudden disappearance… The result was an oneiric but not too enigmatic tale, with remarkable sound design and imagery.

— Isabel Stevens, reviewing from Locarno in our October 2014 issue.

Black Coal, Thin Ice

Black Coal, Thin Ice (Bai Ri Yan Huo, 2014)

Screening Thursday 9, Saturday 11 and Sunday 12

Diao Yinan

China/Hong Kong 2014

With Liao Fan, Gwei Lun Mei, Wang Xuebing

106 mins

A prologue set in 1999 follows recently divorced detective Zhang (Liao Fan, who nabbed the Silver Bear for Best Actor) as he looks into the murder of a man whose body parts have turned up at various coal plants in northern China. An attempt to arrest a couple of suspects ends with four men dead and Zhang wounded and traumatised; five years later, he’s working as a security guard and has the inevitable drink problem. But a new flurry of dismembered corpses prompts him to help his former colleague and keep an eye on a new suspect, the first victim’s widow – with whom Zhang soon, equally inevitably, becomes infatuated. And nothing, of course, is as it seems…

Perhaps the most impressive aspects of Diao’s film are its highly atmospheric use of everyday but striking locations (grim factories, dismal streets and dark alleys, a skating rink) in the wintry coal-mining town and some genuinely surprising eruptions of violence: one blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shootout is especially shocking. (It should be said, however, that notwithstanding the gruesome nature of the murders, the film shows a welcome restraint in what is actually shown.)

— Geoff Andrew, reviewing from Berlin in our April 2014 issue.

The Blue Room

The Blue Room (La Chambre bleue, 2014)

Screening Wednesday 15, Thursday 17, Saturday 18

Mathieu Amalric

France 2014

With Mathieu Amalric, Léa Drucker, Stéphanie Cléau

76 mins

Mathieu Amalric’s approach to his startling adaptation of the Georges Simenon novel The Blue Room takes its inspiration from a passage in the novel’s first chapter: “What he lived through in that half-hour – no, less than that, just a few minutes of his life – was to be shattered into fragments of sight and sound, each of which would be scrutinised microscopically.”

The ‘he’ is Julien (played by Amalric himself), a small-town businessman, and the ‘few minutes’ relate to a seemingly inconsequential conversation he has with his mistress Esther (Stéphanie Cléau) after she bites his lip during a lovemaking session that has dramatic repercussions. The criminal actions, arrest and trial that take place afterwards come at us in shattered fragments indeed – and in a confining, bookish, Academy ratio – with matters of guilt remaining obscure. Beadily impassive throughout, Amalric gives a masterclass in understated angst in this compelling, chilly, if slightly academic crime drama.

— Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

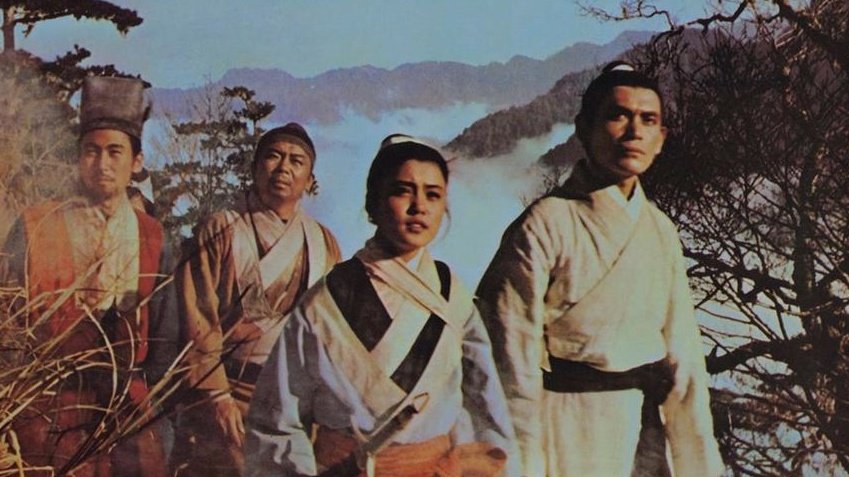

Dragon Inn

Dragon Inn (Long men kezhan, 1967)

Screening Saturday 11, Friday 17

King Hu

Taiwan 1967

With Shi Jun, Shang Kuan Ling-Feng, Bai Ying

111 mins

The operatic wuxia epics made by King Hu in the late 1960s and early 1970s took the martial arts film to lyrical new heights, and boast some of the most breathtakingly choreographed swordplay scenes ever put on film. Alongside other classics like Come Drink With Me and A Touch of Zen, Dragon Inn is a thrillingly enjoyable film that for years has been difficult to see – only available on shoddy, inferior DVD versions when Hu’s films really demand the biggest screen available. This new digital restoration by the Chinese Taipei Film Archive goes some way to correcting those wrongs, and is unmissable for any fans of more recent wuxia titles like Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or Zhang Yimou’s House of Flying Daggers, both of which owe obvious (and acknowledged) debts to Hu’s masterpiece.

— James Bell

Far from Men

Far from Men (2014)

Screening Saturday 18, Sunday 19

David Oelhoffen

France 2014

With Viggo Mortensen, Reda Kateb

97 mins

A solid virtual western, set in Algeria in 1954 and adapted from Albert Camus’s short story ‘L’Hôte’ (which means both The Host and The Guest). Viggo Mortensen is Daru, a Spanish-parented teacher of village children in the Atlas Mountains, who’s given the unwanted responsibility of looking after and escorting an arab prisoner (Reda Kateb – a dead ringer for the young Anthony Quinn) to his almost certain execution. What unfolds is, of course, a relationship of respect building amid several tough moral dilemmas. Requisite aesthetic attention is paid to the harsh landscape (the film was shot in Morocco), the performances are strong and there’s a very effective music score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis.

— Nick James, from Hearts and minds and mumblings: week one at Venice 2014.

From What is Before

From What is Before (Mula Sa Kung Ano Ang Noon, 2014)

Screening Friday 10, Saturday 11 and Wednesday 14

Lav Diaz

Philippines 2014

With Perry Dizon, Roeder Camañag, Hazel Orencio

338 mins

Diaz’s epic chronicles the decline of a remote Filipino village during the years before Ferdinand Marcos’s 1972 declaration of martial law. The film concentrates on small, mysterious tremors that unsettle the community: burning houses, butchered cattle and the unexplained death of a local man; it is reminiscent of Haneke’s pre-WWI-set The White Ribbon – also told in an austere monochrome.

Diaz’s tragedy needs time: at first to establish the pace of agrarian life and the traditions and its inhabitants’ religious and spiritual beliefs; then to wander among the film’s many characters – from the local priest to young tearaway Hakub – before settling on protagonist and sage Sito. Delving into the villagers’ lives, Diaz shows secrets emerging and being buried again, in a film concerned as much with the gap between history and truth as with bringing to light specific and brutal moments in his country’s past.

— Isabel Stevens, reviewing from Locarno in our October 2014 issue.

Girlhood

Girlhood (2014)

Screening Thursday 16, Friday 17, Saturday 18

Céline Sciamma

France 2014

With Karidja Touré, Assa Sylla, Lindsay Karamoh, Mariétou Touré

113 mins

UK distribution Studio Canal

Right from the opening game of American football being played mostly by Franco-African banlieue girls, Girlhood (Bande de filles, which also screened in Directors’ Fortnight) shows Sciamma employing her talents more acutely than ever. Yes, the cliché slow-mo touchdown is there, but she makes us as aware of the shiny too-big helmets and bulky padding as she does of the girls’ athleticism.

Although ostensibly about a ‘girl gang’, the film centres on Marieme (Karidja Touré), an impassive figure who lives with her mother, her bullying elder brother and two younger siblings. Furious to be told by her school that she has no future in further education, she attracts the attention of a small gang run by Lady (Assa Sylla). Marieme loves the attitudinal sense of freedom she gets from these three girls and begins to dress like them with straightened hair (instead of corn rows), a leather jacket and, ominously, with a knife in her back pocket.

Sciamma is non-judgemental throughout as the girls hustle weaker kids for money and rent a hotel room to party in shoplifted dresses. Girlhood has heart-melting but tough performances from Touré and Sylla, seeing girls such as these as a vital force of the future. It’s also gorgeous to look at, and were it not for a slight faltering of momentum in its final quarter would be near-perfect.

— Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

See also Geoff Andrew’s blog post Cannes 2014: girls found and lost – Girlhood and Captives

The Goddess

The Goddess (Shennu, 1934)

Screening Tuesday 14

Wu Yonggang

China 1934

With Ruan Lingyu, Li Keng, Zhang Zhizhi

85 mins

The Goddess boasts what is perhaps the definitive performance by the legendary Ruan Lingyu, one of the greatest stars and finest actresses of the first golden age of Shanghai-based Chinese cinema, who became an icon of female emancipation in China – the archetypal ‘new woman’. Ruan is often referred to as ‘China’s Garbo’, but her presence actually sits somewhere between the ageless modernity of Louise Brooks and the interiority of Garbo. Like Garbo, Ruan was hounded by the tabloid press, the details of her private life pored over and judged, to the point where she could take the strain no more, and she committed suicide aged only 24, only a year after the film’s release.

In The Goddess she plays a women who prostitutes herself to support her young son, and is utterly luminous and magnetic throughout. The new restoration playing here is presented as part of the BFI’s year-long ‘Electric Shadows’ programme of Chinese cinema, and screens with live accompaniment by the English Chamber Orchestra, playing Zou Ye’s new score to the film.

—James Bell

Goodbye to Language

Goodbye to Language (Adieu au langage, 2014)

Screening Monday 13

Jean-Luc Godard

France 2014

With Héloise Godet, Kamel Abdeli, Richard Chevallier

70 mins

UK distribution Studio Canal

In common with all Godard films since Notre musique (2004), Adieu au langage is like one of those notebooks artists keep in movies, with sketches, quotations, colour washes, ideas and doodles tumbling over one another, until finally you reach the not-quite-the-end, with the baby crying and the dog barking. Then some titles. Then the real end, which is a delight.

You may ask why, once you have established that spoken language is too laden with history to have meaning and that the camera image, with its Bazinian one-to-one ontology, is open and even to a certain extent free – why go on making the point over and over? But Godard does it, as ever, with such verve, intelligence and humour, that the result (at, I can now reveal, a brisk 78 minutes) is a visual, cinematic and brain-twisting delight. In 3D.

— Nick Roddick, from Cannes 2014: Ah Dieu, puns Jean-Luc Dogard.

Güeros

Güeros (2014)

Screening Thursday 9, Sunday 12

Alonso Ruizpalacios

Mexico 2014

With Sebastián Aguirre, Tenoch Huerta, Leonardo Ortizgris

106 mins

Alonzo Ruizpalacios’s Güeros impressed against my suspicion that it might be show-offish. The narrative begins when troublesome teen Tomàs is packed off by his fed-up mother to his brother Sombra’s wrecked powerless student residence in Mexico City. Although Sombra is a dark-skinned Mexican, his best friend Santos and Tomàs are both classified as güeros – an insult-term for the light-skinned.

Essentially a road movie, with regular elisions into dreamlike situations, set within the expansive confines of Mexico city at a time when a months-long student strike has occupied the National University, Güeros sees the three young men shake off their listlessness when, joined by Sombra’s female DJ crush, they set out to find the dying legendary folk-rock singer Epigmenio Cruz, who once, it’s said, “made Bob Dylan cry”.

As self-aware black-and-white, nouvelle-vague-tribute fever dreams go, Güeros is surprisingly beautiful, inventive and convincing.

— Nick James, from Tribeca 2014: basketball and the city.

Hungry Hearts

Hungry Hearts (2014)

Screening Tuesday 14, Thursday 16 and Friday 17

Saverio Costanzo

Italy 2014

With Adam Driver, Alba Rohrwacher, Roberta Maxwell

109 mins

Saverio Costanzo’s Hungry Hearts arrests attention in a confined way. Italian Embassy worker Mina (Alba Rohrwacher) enters the small loo of a New York Chinese restaurant, realises there’s a guy in the stall having a digestional crisis, and tries to leave but the door jams. Jude (Adam Driver) emerges horribly embarrassed at the smell he’s made, but before you know it, they’re in a relationship. The embassy wants to transfer Mina out of New York but she gets accidentally pregnant and they marry. These early set-up scenes are superb – the acting is compelling and beguiling – but when the film turns into a battle over the weight of their baby son, with Mina turning out to be such a homeopathic medicine nut that she endangers the kid’s life, the characters become decreasingly plausible.

— Nick James, from Hearts and minds and mumblings: week one at Venice 2014.

It Follows

It Follows (2014)

Screening Saturday 11, Monday 13

David Robert Mitchell

USA 2014

With Maika Monroe, Keir Gilchrist, Daniel Zovatto, Jake Weary

100 mins

UK distribution Icon Film Distribution

It Follows combines the sexual paranoia of the 80s slasher flick with something of Cherry Falls’s more sex-positive set up, and adds its own intriguing moral twist. After Jay (Maika Monroe) sleeps with a new boyfriend, he explains he has passed her a sort of hex whereby she will now be followed by something that had been following him. If she sleeps with someone else, that person will become the new target – but she must beware: when a victim is killed by the malevolent presence, it will shift its attention back to the last link in the chain. The question becomes: would you sleep with somebody knowing you might be sentencing them to death?

It’s to writer-director David Robert Mitchell’s credit that this contrived-sounding setup plays very naturally onscreen and never devolves into a hand-wringing allegory for sexually transmitted disease (it’s there, but worn lightly). He even manages to throw in a few more rules – it cannot run, it can only walk; it can look like anyone it wants; it’s invisible to those it’s not targeting – without getting bogged down in J-horror style exposition. (Ju-On and Ringu are the sorts of films whose underlying premises It Follows most recalls, but it’s more slyly enigmatic than either.)

— Catherine Bray from Horrifying Cannes 2014: It Follows.

Jauja

Jauja (2014)

Screening Friday 17, Sunday 19

Lisandro Alonso

Argentina-USA-Netherlands 2014

With Viggo Mortensen, Viibjork Mallin, Ghita Nørby

101 mins

UK distribution Soda Pictures

This is Lisandro Alonso’s first foray into costume drama, and employs Viggo Mortensen’s star-power; but the Argentine filmmaker’s austere style shows no signs of softening. In fact this John Ford-esque western, set in 19th-century Patagonia, is far stranger than anything he’s produced before.

Captain Dinesen (Mortensen), a Danish soldier-engineer, is a wandering soul, searching at first for a utopia (Jauja, the film explains at the start, is a mythical paradise) and then for his daughter, who has run off with a trooper. Alonso painstakingly plots Dinesen’s journey, riding in and out of the frame in real time as the landscape gradually changes from lush grasslands to a craggy void (beautifully shot in Academy ratio). As he ventures deeper into the wilderness, Alonso’s slow cinema ventures down the rabbit hole, his Heart of Darkness fable turning into a Lynchian riddle.

— Isabel Stevens, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

Leviathan

Leviathan (2014)

Screening Tuesday 14, Friday 17

Andrey Zvyagintsev

Russia 2014

With Alexey Serebryakov, Elena Lyadova, Vladimir Vdovitchenkov

140 mins

UK distribution Artificial Eye

A Russian tale of outlying corruption and despair, Andrei Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan won the Best Screenplay prize at Cannes this year. Its hero, Kolia (Alexei Serebriakov), is a drunk who owns a large wooden house and auto-repair shop that is coveted by the equally bibulous local mayor, Vadim (Roman Madianov), for a development project. Even in his drunken rages, Kolia constantly proclaims his love for his wife, Lilya (Elena Lyadova), a fish factory worker, and for the house itself. Vadim tries to buy Kolia off, but he won’t budge, forcing the mayor through appeal after appeal before he finally hires Dmitri (Vladimir Vdovitchenkov), an ex-army buddy turned lawyer, from Moscow, to dig up dirt on him.

What spills out from this scenario is an epic of blackmail, betrayal, random thuggery and family resentment that’s chilling and absorbing by turns. Black humour helps us through the heavy symbolism (Russia as picked-to-the-bone whale, ruled by the triumvirate of state, church and money). The speed with which, for instance, the local magistrate reads her verdicts could rival any stock auctioneer.

— Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

See also Geoff Andrew’s blog post Cannes 2014: big fish to fry – Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan

Maidan

Maidan (2014)

Screening Saturday 11, Monday 13

Sergei Loznitsa

Netherlands-Ukraine 2014

133 mins

Sergei Loznitsa’s astonishing documentary records the events in Kiev’s Maidan Square between November 2013 and March 2014. Imagine that you’re seeing real history unfold, with real struggles, battles and deaths, but in a series of moving-image Breughel paintings: that’s how Maidan makes its case. How anyone could have set up so many carefully framed locked-down cameras – most, unbelievably, close to violent action, others at a god-like panoramic distance – is a minor miracle.

The major event is the people’s struggle itself. Loznitsa does not shrink from the violence inflicted on the police and nor would he think about cutting out people dying at the hands of police marksmen. The images combine the banal and the dramatic as only documentary images can. The effect is cumulative, a build-up of impressions not overly driven by sensation. It’s as powerful as anything in Herzog’s canon.

— Nick James, reviewing from Cannes in our July 2014 issue.

See also Neil Young’s blog post News from the front: Odessa 2014

My Darling Clementine

My Darling Clementine (1946)

Screening Thursday 9, Saturday 11

John Ford

USA 1946

With Henry Fonda, Linda Darnell, Victor Mature

97 mins

John Ford’s magnificent telling of events at the town of Tombstone, Arizona that lead to the famed gunfight at the O.K. Corral between (as played here) Henry Fonda’s heroic Wyatt Earp, Victor Mature’s Doc Holliday and their foes the violent Clanton family has been newly restored by Fox archivist Schawn Belston from a 35mm fine-grain master print held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the result is spectacular, particularly on the big screen. As critic Tag Gallagher has noted, the classic conventions of the Ford western are here often pushed into exaggerated, expressionist registers, and the restoration brings out the rich blacks and luminous whites of the film’s cinematography. ‘Iconic’ is a word that often gets thrown at westerns, but here it’s properly justified. Sublime.

— James Bell

National Gallery

National Gallery (2014)

Screening Sunday 12, Tuesday 14

Frederick Wiseman

USA-France 2014

173 mins

UK distribution Soda Pictures

Most of Frederick Wiseman’s recent work has centred on institutions the 84-year-old documentarian clearly admires. Joining the roll call of Berkeley campus, a boxing gym in Texas and the Paris Opera Ballet comes London’s National Gallery, into which Wiseman clearly relishes delving. His three-hour portrait is not only an immersive behind-the-scenes tour, highlighting the unseen work behind the hangings, but also an essay on the art of visual storytelling.

Some of the film’s most fascinating moments pay tribute to the gallery’s technical prowess and craftsmanship: employees intricately analysing and retouching an artist’s brushstrokes under the microscope, hand-chiselling huge, ornate frames and making minute alterations to gallery lighting. Interestingly, the private preservation scenes yield as much information as the public lectures that punctuate the film. Wiseman draws our attention to the overlooked: the shadows in negative space that are fundamental to our reading of the painting; another (recycled) Rembrandt under the surface of his portrait of merchant Frederick Rihel which lay unnoticed for hundreds of years until technology allowed it to be spotted.

— Isabel Stevens, from Cannes 2014: behind the scenes at the museum – Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery.

Ne me quitte pas

Ne me quitte pas (2013)

Screening Sunday 12, Tuesday 14

Sabine Lubbe Bakker, Niels van Koevorden

Netherlands-Belgium 2013

107 mins

Lubbe Bakker and van Koevorden’s droll nonfiction tragicomedy tracks the odd-couple comradeship of two Belgian farmers – hangdog Fleming Bob and Walloon cowboy Marcel – who have been left to pickle themselves in drink (the film opens with Bob’s wife taking their kids off to live with another man, though you assume Bob’s alcoholism is as much cause as effect of his isolation).

The film follows them over many months of village-life trials and misadventures, though the recurring motif is the mano-a-mano dinner-table set up and the extended conversations that regularly return to insouciant discussions of suicide. With its deadpan ambivalence and unerring unpredictability, it’s a portrait of rural male mid-life solitude that’s fresh, funny and troubling.

— Nick Bradshaw

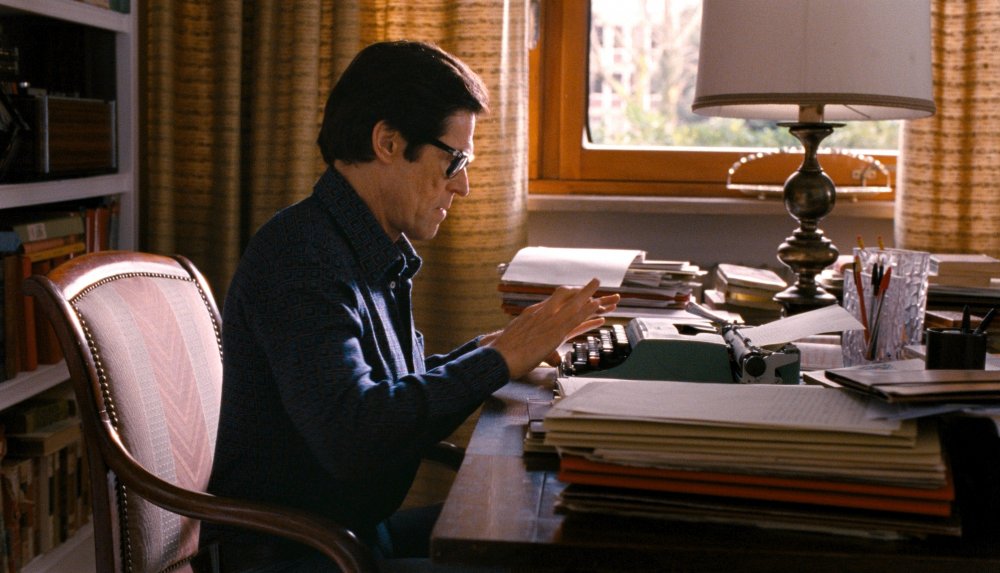

Pasolini

Pasolini (2014)

Screening Friday 10, Saturday 11, Monday 13

Abel Ferrara

France-Italy-Belgium 2014

With Willem Dafoe, Ninetto Davoli, Riccardo Scamarcio

87 mins

Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini imagines the last day in the life of Italy’s most passionate director, evoking too the unrealised projects that may have been running through his mind as his day moved towards his notorious murder. The largely Italian audience I watched it with gave the film a muted reception. Those I spoke to afterwards put that down to the film’s one-day focus, its jumping between English and Italian speech and choice of a homophobic murder rather than the political killing many believe (or want to believe) happened.

As a detester of the average biopic, however, I enjoyed Pasolini’s inventive interleaving of a many-threaded identity into one succinct 83-minute experience: Dafoe incarnates the director’s hard-edged look, his voice has the right authority and the 70s-style dark-lit-corridor cinematography gives it the right kind of elegance and polish.

— Nick James, from The Golden Lion for A Pigeon…: Roy Andersson glides to the prize at Venice 2014.

The Princess of France

The Princess of France (La princesa de Francia, 2014)

Screening Thursday 9, Friday 10

Matías Piñeiro

Argentina 2014

With Julián Larquier Tellarini, María Villar, Agustina Muñoz

70 mins

Matías Piñeiro’s The Princess of France continues with the milieu and subject matter established by his last two films, Viola and Rosalinda: middle-class twenty-somethings staging Shakespeare in a cultured Buenos Aires bubble. This 70-minute screwball romance wraps itself around Love’s Labour’s Lost: protagonist Víctor echoes Ferdinand, King of Navarre, in swearing off women, but gets enveloped in a love heptagon with the actresses of his radio adaptation of LLL.

The film is not the stuffy study of male lust that this might suggest, its delightfully twisting plot and imaginative close-up camerawork zipping between perspectives and love trysts, paying equal attention to this scheming, incestuous clique’s women and their desires. The ending doesn’t quite deliver the melancholy punch it should, or equal the bombast and invention of the choreographed football match in the film’s opening scene, but the snappy, in-love-with-language dialogue had me charmed.

— Isabel Stevens, reviewing from Locarno in our October 2014 issue.

La Sapenzia

La Sapienza (2014)

Screening Monday 13, Wednesday 15

Eugène Green

France-Italy 2014

With Fabrizio Rongione, Christelle Prot Landman, Ludovico Succio

107 mins

A nimble, high-cultured tale, combining drama with a Grand Tour-style travelogue around the churches, chapels and cloisters of the Baroque Italian architect Francesco Borromini. With his unrelenting stare, Fabrizio Rongione dominates the film as Alexandre Schmidt, a cold and abrupt Borromini-obsessed starchitect. On tour in Italy, he and his wife Aliénor meet Goffredo, a young architecture student, and his sister Lavinia. Alexander reluctantly adopts Goffredo, and the film splits in two: while the two men go off on tour, Aliénor stays to nurse the fragile Lavinia back to health while contemplating her strained relationship with her husband.

Schmidt’s lectures on Borromini, and Goffredo’s precocious ruminations on space and light are the film’s highlights, accompanied by some audacious camera work, gliding over the contours of Borromini’s creations, which are bathed in a piercing light. At times it resembles Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours, another philosophical essay emerging out of a story about two strangers meeting and talking; but Green’s is a more mannered fable, full of intricate mises en scène, the rigorous symmetry with which he positions his characters echoing Borromini’s staunchly geometrical compositions. La Sapienza’s spiralling story collapses into its subject matter in intriguing and surprising ways and in its search for meaning in life and art the film produces some sublime moments, but never takes itself too seriously.

— Isabel Stevens, reviewing from Locarno in our October 2014 issue.

’71

’71 (2014)

Screening Thursday 9, Friday 10

Yann Demange

UK 2014

With Jack O’Connell, Paul Anderson, Richard Dormer

96 mins

UK distribution Studio Canal

Yann Demange’s ’71 is a taut, insightful, moves-at-a-clip thriller set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. Its premise is simple: Gary Hook (an excellent Jack O’Connell) is a wounded, disarmed private left behind by his unit in the Falls Road area of Belfast. When a well-connected Protestant child inadvertently leads him further into danger, Hook finds that the Provos want him dead, the traditional IRA want to get him to trade him, the UDA couldn’t care less and the murderous undercover units of the British army find him an inconvenience.

In stark Darwinian terms, the film lays out how compromised, ruthless and determined to be right everyone involved in the Troubles was, but it always puts a bewildered, battered humanity to the fore. ’71 is every bit the gripping intrigue drama one hoped for, as splashily imagined as the best night-time graffiti and good at wrong-footing viewers’ expectations.

— Nick James, reviewing from Berlin in our April 2014 issue.

Theeb

Theeb (2014)

Screening Saturday 11, Friday 17

Naji Abu Nowar

Jordan-UK-UAE-Qatar 2014

With Jacir Eid, Hassan Mutlag, Hussein Salameh, Jack Fox

100 mins

Venice’s one charming discovery was what people are already calling an ‘Arab western’ and yes, newcomer Naji Abu Nawar’s Theeb fits that description but I saw it more as an antidote to the imperial swagger of Lawrence of Arabia. Set in the same time and place as Lean’s great epic, Theeb follows the fortunes of the titular feisty young Bedouin boy who, when his brother is asked to guide an Englishman across the desert, secretly tags along. The Englishman carries a brown wooden box whose significance Theeb cannot fathom. Then he witnesses ambush and disaster at a well and must find a way to survive the desert on his own. It’s a taut surivival yarn directed by a sure hand.

— Nick James, from The Golden Lion for A Pigeon…: Roy Andersson glides to the prize at Venice 2014.

Timbuktu

Timbuktu (2014)

Screening Friday 10, Saturday 11

Abderrahmane Sissako

France-Mauritania 2014

With Ibrahim Ahmed, Toulou Kik, Abel Jafri, Fatoumata Diawara

97 mins

It’s eight years since Abderrahmane Sissako made Bamako (2006), 12 since Waiting for Happiness (2002) and 16 since Life on Earth (1998): all very different movies, but all discernibly his, distinguished by their elliptical, oblique approach to narrative and theme, by their subtle, imaginative but finally very direct take on political, economic and ethical issues and by their quietly meticulous, detailed deployment of image and sound. Each looks at contemporary African life with a deceptively dispassionate eye: Sissako is rightly wary of apportioning blame in a unambiguous fashion, and makes quite clear that questions of cause and effect are complex and should never be answered simplistically.

His latest film Timbuktu is inspired by the horror he felt at the real-life stoning to death, in July 2012, of an unmarried couple living in Aguelhok in northern Mali and is characteristic of his work on many levels. It sort of centres on the experiences of Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed), Salima (Toulou Kiki), their daughter Toya and their young cowherd Issan – whose sudden, accidental loss of control of a pregnant cow results, tragically, in several deaths – but the film takes in a far wider range of characters and narrative strands. Though confronting extremist intolerance and sometimes murderous injustice, Sissako consistently and deftly avoids clumsily simplistic characterisation.

— Geoff Andrew, from Cannes 2014: crying Timbuktu.

The Tribe

The Tribe (Plemya, 2014)

Screening Wednesday 15, Friday 17

Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy

Ukraine 2014

With Grigoriy Fesenko, Yana Novikova

132 mins

Half Lord of the Flies, half St Trinian’s, writer-director Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy’s ferociously confident feature-debut dominated Critics’ Week at Cannes this year, taking the Grand Prix, two other awards and across-the-board euphoric reviews. Amply confirming the promise of Slaboshpytskiy’s Locarno-garlanded, wordless short Nuclear Waste (2012), it likewise dispenses with spoken dialogue to recount the chillingly humorous shenanigans at a Kiev boarding-school for the severely hearing- and speech-impaired.

Co-produced, edited and shot by another leading light of what we may tentatively dub the ‘Ukrainian New Wave’, Valentyn Vasyanovych – responsible for the starkly elegant widescreen compositions and gliding Steadicam manoeuvres – the film audaciously dispenses with subtitles, but those unfamiliar with Ukrainian Sign Language will soon get the gist of what’s going on. Jarringly direct in its presentation of violence, sex and harrowing subject-matter and featuring a slew of outstanding performances from its youthful non-professional cast, The Tribe eschews the pitfalls of gimmickry by applying consistently rigorous control to a boldly original concept.

— Neil Young

White God

White God (Fehér Isten, 2014)

Screening Friday 10, Sunday 12, Monday 13

Kornél Mundruczó

Hungary-Sweden 2013

With Zsófia Psotta, Sándor Zsótér, Lili Horváth

119 mins

UK distribution Metrodome Group Ltd

The story of a young girl and her dog, it starts like a Disney family film, develops into a horror movie (George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead is explicitly referenced) and turns into an apocalyptic vision which would at once delight and confound Morrissey, with animals striking back against human hegemony.

To summarise the plot in brief: 13-year-old Lili (Zsifia Psotta, quite extraordinary) is dumped on her father (Sàndor Zsótér) when her divorced mother flits off to Australia. He refuses to let Lili keep her beloved dog, Hagen (Luke), and angrily casts him adrift in contemporary Budapest.

Having learned how to survive, Hagen is, in swift succession, seized by a breeder of fighting dogs, becomes a champion killer under the name of Max (played by a second dog called Body), leads a break-out from the dog pound, and becomes leader of a pack that eventually holds the city to ransom. What’s so impressive is the way Mundruczó switches gears, from the family flick featuring a lost puppy dog – a kind of canine version of Baby’s Day Out – to a gothic register as the former pet struggles between his ‘Doctor Hagen’ and ‘Mr Max’ personalities.

— Nick Roddick, from Cannes 2014: regards of the week – Amour fou, Force majeure and White God.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.