‘Crisis’ is probably not too strong a word to describe what the South Korean Left went through in the 1990s. The Left had taken shape in the 70s and 80s, mostly in intellectual and labour-activist circles, as a movement opposed to the country’s successive military governments. It became a militant, student-led movement after the 1980 massacre of unarmed civilians on the streets of Gwangju. Anyone around in the 80s will remember TV news images of pitched battles between student demonstrators and heavily armoured riot police on the streets of central Seoul, often blanketed in smoke from Molotov cocktails and clouds of tear gas. (The only time I’ve ever been tear-gassed myself was on one of my early visits to Seoul in the late 80s: I hadn’t been demonstrating but stumbled into pockets of the invisible gas while making my way along Euljiro back to my hotel in Myeongdong. Korean friends advised me to spread toothpaste on a facemask for protection if it ever happened again.)

The London Korean Film Festival’s Documentary Fortnight: Another World We Are Making ran 11, 12, 18 and 19 August 2018 at the Birkbeck Cinema and Korean Cultural Centre UK.

The main London Korean Film Festival 2018 runs 1-14 November in London and 16-25 November in venues around the UK. Preview screenings have been running all year.

Since the student Left of the 80s and early 90s routinely disbelieved everything the South Korean government told them, they assumed that the constant stream of anti-communist propaganda in the media was false and took a detached but generally benign view of North Korea. Despite the shift to more legitimate, civilian-led government in 1993, these attitudes persisted through the 90s and didn’t really change until the veteran opposition leader Kim Daejung became president in 1998. His ‘sunshine policy’ promoted engagement with the North, and delegations of ‘specialists’ in various fields were invited to visit Pyongyang.

One such was a delegation of film industry personnel (led by people with well-known leftist sympathies, such as the actor/producer Myung Kaynam), and it was only when that delegation returned to Seoul with the bad news that co-operation with the North would be impossible for decades to come that disillusionment with the North began to set in. This did eventually produce a crisis of sorts in South Korean leftist circles, and the thinking about domestic politics and social activism has changed substantially as a result.

Sang-kye-dong Olympics (1988)

Aside from a few indie filmmakers with ambitions to turn professional (such as Jang Sunwoo and Park Kwangsu), hardly anyone in the student movement of the late 1980s gave any thought to the heavily controlled and censored commercial film industry, where the dozen or so companies licensed to produce films were required to make the occasional anti-communist movie. Instead an independent, underground cinema sprang up, showing 16mm shorts and features in halls where the police wouldn’t notice. That generally meant university campuses and union premises, but I went to one such screening in an upmarket hotel ballroom in Daegu in 1988. Nothing very inflammatory was shown on that occasion, but the films did have a clear oppositional stance. When civilian government arrived in 1993 the underground filmmaking movement quickly gave way to South Korea’s current independent cinema, which has both fiction and documentary wings and is fed by graduates from the university film courses which have proliferated across the country.

Kim Dongwon at the London Korean Film Festival in August

Kim Dongwon, a Catholic social activist, became an important figure in underground agit-prop when he got involved with (indeed, started living with) villagers in Sang-kye-dong whose homes were compulsorily purchased and demolished in the run-up to the 1988 Seoul Olympics. He picked up a video camera and began documenting their failed attempts to resist the still-militarist government. The resulting tape, Sang-kye-dong Olympics (1988), looks quite unsophisticated and ramshackle now, but it seeded the many subsequent films and videos which have recorded and participated in activist struggles against the state; Kim himself came to be seen as a kind of godfather to the entire radical documentary movement in Korea.

He was the main guest at a two-weekend event in London in August, organised by the Korean Cultural Centre to replace the documentary strand in its annual London Korean Film Festival, and took part in Q&As and a panel discussion at Birkbeck College; his latest film was screened at the Korean Cultural Centre a week later. Professor Nam Inyoung of Dongseo University in Busan was around to provide an historical perspective on activist filmmaking, and films from two younger teams who are now working hand-in-glove with local activist groups were also screened.

Six Day Fight at Myong Dong Cathedral (1997)

The Sang-kye-dong villagers took refuge from the riot police in mid-June 1987 in the grounds of Myeong-dong Cathedral in central Seoul where they were joined by students protesting the dictator Chun Doohwan’s announcement that his designated successor was ex-general Roh Taewoo; the six-day sit-in initially had the support of one faction in Korea’s Catholic church. Kim Dongwon followed them there and kept filming, but didn’t edit the material until a full decade later: Six Day Fight at Myong Dong Cathedral (1997) was screened alongside Sang-kye-dong Olympics at Birkbeck. By 1997, when the civilian presidency of Kim Youngsam was coming to an end, the fractious and often violent political struggles of the late 1980s were receding into what leftist Koreans tend to call ‘the dark years’. Kim’s ten-years-later documentary took account of the new political reality. It was less a call to arms than an analysis of the unhealed wounds, including those within the Catholic church. The film includes retrospective testimony from both activists and clerics.

Kim Dongwon’s journey from fairly primitive agit-prop to a more reflective and analytic style of documentary-making took place against what I described at the start as the crisis in the South Korean Left: the gradual abandonment of the image of North Korea as a viable alternative system, the awkward coming-to-terms with liberal and more accountable civilian government, and a growing sense that straightforwardly polarised politics weren’t meeting South Korea’s changing needs. In absorbing these developments and reflecting them in his work, Kim Dongwon made himself an exemplary filmmaker for the times. His film Repatriation (Songhwan, 2003), also screened at Birkbeck, is very probably the most consequential documentary made in South Korea since the transition to civilian democracy.

What makes Repatriation special is its mixture of personal testimony and political analysis. Kim Dongwon met political prisoner Cho Changson when he was released from jail in the early 1990s. Cho had been locked up for 17 years as a North Korean spy; he was one of several ‘unconverted’ prisoners (meaning those who had resisted anti-communist indoctrination in prison) released at the time, all petitioning for the right to rejoin their relatives in North Korea.

Repatriation (Songhwan, 2003)

Filming across the 90s, Kim documents the efforts of the support network around the ex-prisoners to improve their lives and find new tactics to advance their case for repatriation. Kim himself is an important member of the support group and he gradually develops a close relationship with Cho in particular; Cho later says that Kim was “like a son to me”. But when the ex-prisoners are finally allowed to leave at the end of Kim Daejung’s presidency, neither the North nor the South is willing to allow Kim to be there to film the reunions in Pyongyang; Kim is forced to ask someone else to record the ‘homecoming’ and to carry video messages back and forth. The strong emotional ties between Kim and Cho are the core of the film. By the end, both men recognise poignantly that they are unlikely ever again to meet face-to-face.

On the way to this bittersweet finale, the film’s narration (written and spoken by Kim himself) acknowledges all the political Catch-22s. He shows clips of the ex-prisoners from television and newsreel coverage, stridently hostile in tone and stance, and explains how alien it seemed to his own first-hand experiences with the men. But he also admits his misgivings about intruding into their private feelings and his bafflement at their loyalty to a political system by then known to be deeply inhumane and untrustworthy.

Since his own warmth towards Cho, a remarkably good-humoured man, is central to the film, Kim can empathise with Cho’s longing to be reunited with long-unseen relatives. But this resonates awkwardly with Kim’s own commitments to democracy and political accountability; his candour in discussing his personal political doubts and confusions inevitably reflects the larger identity crisis of the South Korean Left under left-liberal presidents.

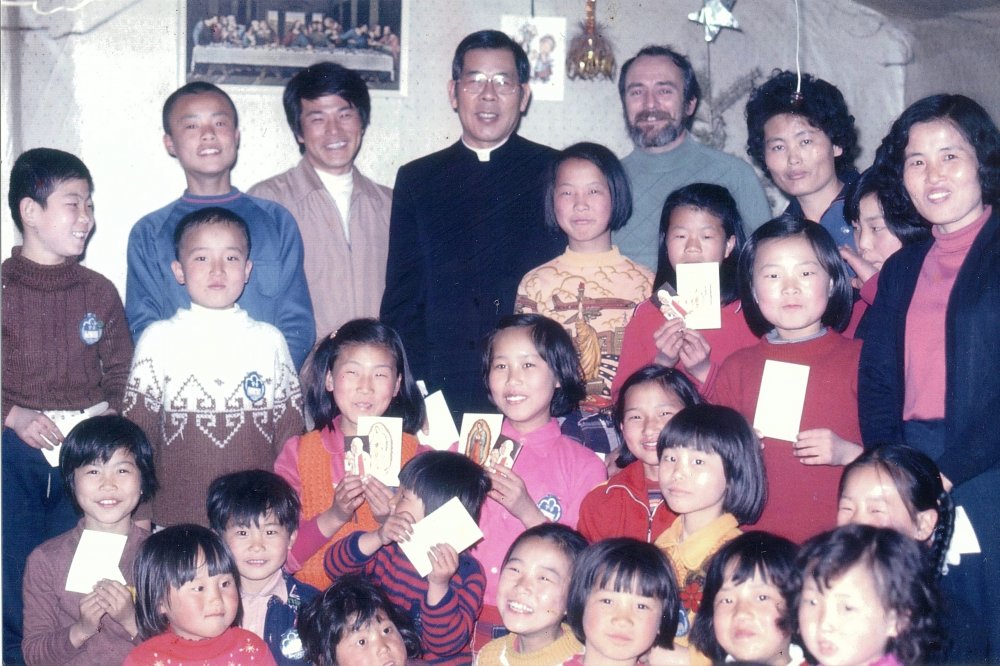

Jung-Il-Woo, My Friend (2017)

One of Kim’s newest films, shown the following weekend, adds the issue of religious faith to the political conundrum. Jung Il-Woo, My Friend (Nae Chingu Jeong Ilwoo, 2017) is a heartfelt tribute to the Jesuit missionary John Daly, from Illinois, who came to South Korea in the 1950s and ‘went native’ to the extent of adopting a Korean identity as Jung Il-Woo.

Sometimes embarrassing his seniors in the church, Daly was a social and political activist who supported impoverished communities and joined political protests – incidentally providing Kim Dongwon himself with a role model. But although the film includes testimony from Daly’s relatives and friends in Illinois, it shies away from asking the difficult questions that will strike many Western viewers. It doesn’t examine the impulses which drove Daly’s decision, and never queries the Jesuit belief that poverty and victimhood brings people closer to their god. Such blind-spots prevent the film from achieving the international ‘reach’ of Repatriation, but they also confirm that Kim Dongwon’s art is nowadays rooted in humanist empathy rather than political ideology.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.