Joaquin Phoenix is 44 years old, with 35 movie credits (more than half of those in leading roles), one Golden Globe (for playing Johnny Cash in Walk the Line) and three Oscar nominations (for Gladiator, Walk the Line and The Master). He has gone by two names – in his earliest screen appearances, he was ‘Leaf’ before reverting for good to his birth name in 1995 in Gus Van Sant’s To Die For – and has had two retirements from acting so far.

This feature is also available in our November 2019 issue

One was authentic (when he jacked it all in at the age of 16 to ride horses and work on a farm: “Just growing up,” he called it) and one staged, when he quit the business in 2008 to become a hip-hop star. That volte-face turned out to be merely the raw material for a 2010 mockumentary, I’m Still Here, in which a character called ‘Joaquin Phoenix’ ditches a successful acting career to pursue hip-hop, only to encounter incredulity and mockery at every turn.

Phoenix is loyal: he has made four films with the director James Gray (The Yards, 2000; We Own the Night, 2007; Two Lovers, 2008; The Immigrant, 2013) and two each with Paul Thomas Anderson (The Master, 2012; Inherent Vice, 2014), Van Sant (the second was Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, 2018) and M. Night Shyamalan (Signs, 2002; The Village, 2004). Shyamalan said of him in 2002: “If he wanted to, he could be the biggest actor in the world.”

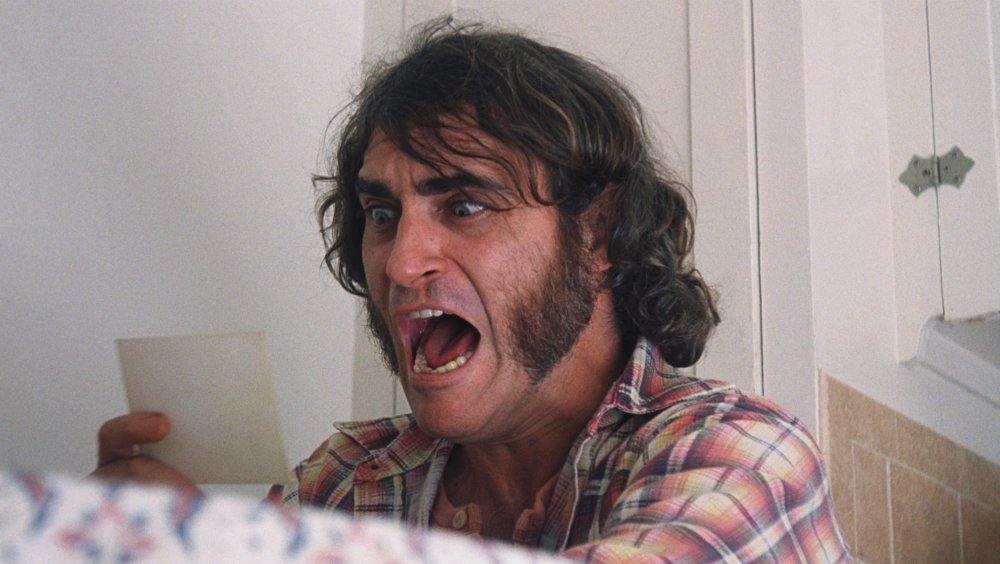

Whether he wants to is moot, at least now that he has played Arthur Fleck, the physically bruised, psychologically damaged part-time clown and aspiring standup of Joker, a clammy character study with delusions of Taxi Driver. The movie is like Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’ in reverse. Arthur begins the story as an insect scuttling through the streets and being routinely crushed underfoot, and ends it as something approaching a figurehead for the dispossessed and deplorable.

The Joker (2019)

Joker won the Golden Lion at Venice in September and will by now be hogging multiplex screens across the world by posing, Trojan horse-style, as a comic-book origin story. And yes, it is that – the director Todd Phillips matches up the end of the movie, more or less, to the flashbacks in Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman.

More notable is how fully the picture is steered by Phoenix’s qualities and range, as well as his need to roam beyond them with every performance. “Our goal was never to introduce Joaquin Phoenix to the comic-book universe,” Phillips has said, “but to introduce comic-book movies to the Joaquin Phoenix universe.”

Mission accomplished. Even after having made the movie, Phoenix remains distinct from, and splendidly oblivious to, the implications of appearing in a product with comic-book roots. Asked by Dave Itzkoff of the New York Times whether it was a bad sign for cinema that character-driven movies can only get made if they contain some pre-sold pop-culture hook, he growled: “I don’t even know what you just said.”

Signs (2002)

It’s telling that Shyamalan chose the word ‘actor’ in his 2002 prediction, perhaps knowing even then that Phoenix would never countenance the level of surrender necessary to become a ‘star’. Physically, he is too mutable and enigmatic to succumb to stardom.

His physiognomy is a puzzle. To gaze at Tom Cruise or Will Smith is to be reassured by symmetry; to look upon Phoenix, with his Mount Rushmore brow, hyper-intense X-ray stare and nose like a falling arrow is to be confronted with dramatic and infinite riddles. The critic Anthony Lane wrote in the New Yorker of the “tense, oddly compacted expression on his face, as if his head were caught in an invisible vice”. Gray has described Phoenix as “ambiguous, good-looking but slightly off-centre, with a tragic quality” and has noted his “inner Beelzebub” – which Joker has now surely coaxed into the open.

You Were Never Really Here (2017)

Like any serious actor worth his salt – and his sugar – he has piled on the pounds with no thought for vanity. In Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here, the camera admires his bare unruly bulk and finds unspoken stories in his gone-to-seed flesh. Many of his films make room for that moment when he unveils the particular body he has arrived at this time around. (It’s the equivalent of hearing a new Meryl Streep accent.)

The convention was started by To Die For, in which the camera moves down Phoenix’s torso and then hovers tantalisingly over his navel; as the critic Adam Mars-Jones pointed out in the Independent, “It looks like shorthand – that’s as much as we can show you, folks – until you realise that the camera finds Phoenix’s tensed midriff rewarding in its own right.”

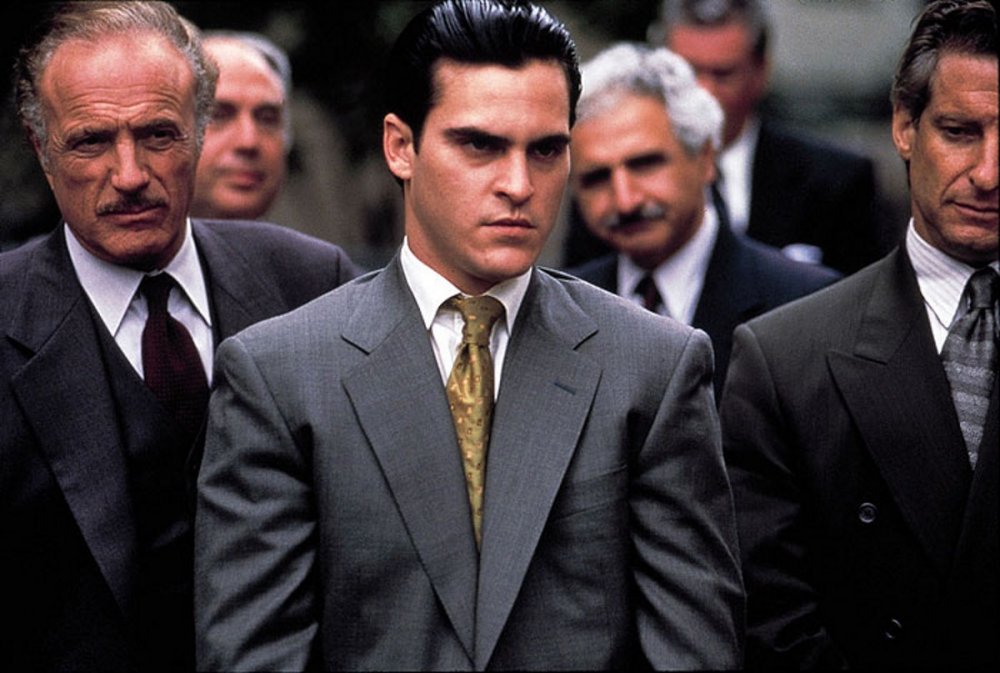

He strips in broad daylight during a clandestine meeting in The Yards – what better way for a criminal to prove he’s not wearing a wire? – and Joker, too, has its share of shirtless shots that testify to his dedication in the area of weight-loss: he makes the Pale Man from Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) look like a Calvin Klein model.

The Yards (2000)

Watching Phoenix as the emperor Commodus in dailies for Gladiator (2000), Ridley Scott famously exclaimed: “Fuck, you got fat!”

But he can be strikingly graceful too. In Joker, he keeps breaking out into dance routines; on a flight of concrete stairs, he negotiates each one with the liquid elegance of a Slinky, and performs a soft-shoe shuffle on a subway platform while a cop is beaten to death in front of him.

In a scene near the start of We Own the Night, he somehow manoeuvres himself out from behind the wheel of a car, across the passenger seat, through the window and on to the pavement in one seamless movement; the effect is like watching tequila magically pouring itself from the bottle.

We Own the Night (2007)

More than 30 years as an actor should be enough time to have tamed his eccentricities and sanded down his abrasiveness. But it hasn’t. At the time of writing, it has just been reported that he walked out of an interview with the Daily Telegraph in response to a question about whether the violence in Joker, connected as it is to a social movement of spurned and resentful men, might inspire copycat behaviour. Stars don’t storm out of interviews: they turn up early to premieres to kiss babies and take selfies.

Nor do they mislead and obfuscate, whether it’s on the grand scale of I’m Still Here or the more mundane one of fabricating biographical details. Phoenix has publicly announced two engagements in his life, one real (he is currently engaged to the actor Rooney Mara) and one fake: in 2015, he let slip that he had recently proposed marriage to his girlfriend. Asked some months later why he had lied about this, he explained: “I wanted the audience to like me. And they always like you when you get engaged. Everyone applauds.”

That line would sit easily on the lips of Arthur Fleck, who is pure neediness, all jutting rib-cage and exposed nerve endings. But it doesn’t sound very much like Phoenix. Vulnerable though he often appears, he has seemed never to want anything from the audience, least of all their approval.

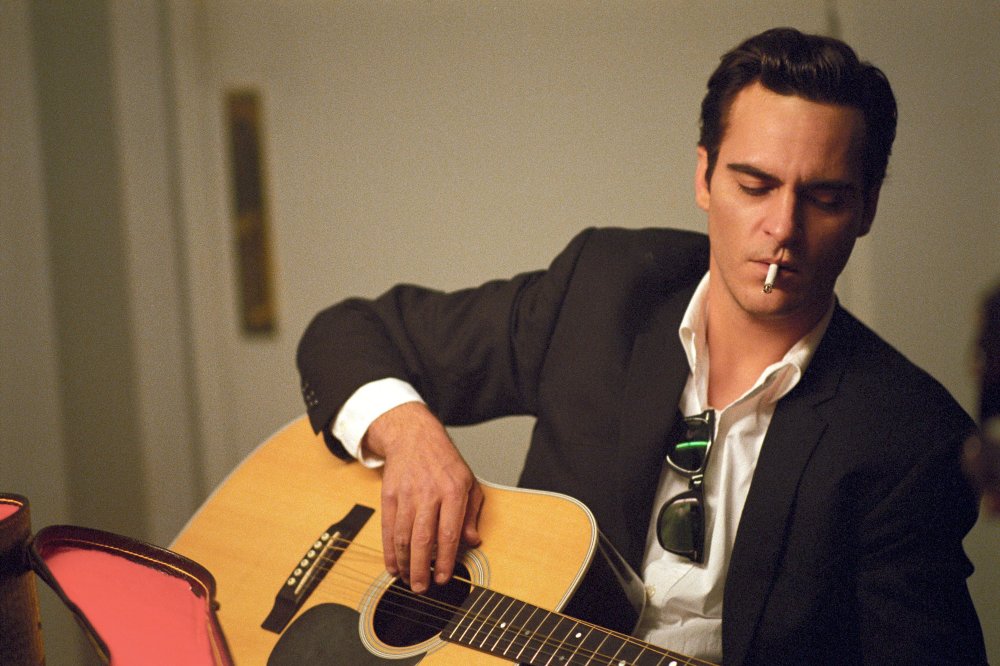

Walk the Line (2005)

It has been said that he only connected with the part of Johnny Cash in Walk the Line (2005) once he was told (rightly or wrongly) that It Ain’t Me, Babe, the Bob Dylan song that Cash positively spits into the microphone, was written from the point of view of an idol addressing his adoring fans: “I’m not the one you want, babe / I will only let you down.” That sounds more like it. That’s very Joaquin Phoenix.

It’s not that he isn’t dependable. He may have consented to half-baked films – most recently Woody Allen’s Irrational Man (2015), where he tapped for the first time into a latent air of superiority to play an amoral professor – but you can never accuse him of a poor or uncommitted performance.

Rather, it is the whims or enthusiasms of fans and critics that appear to set his teeth on edge, and which act on him like a depressant. Wasn’t the point of I’m Still Here to reject all that, to start again, to push away the admirers with their stifling expectations and not only court ridicule but embrace it, kiss it, dive into it?

I’m Still Here (2010)

As this suggests, it is his proximity to the absurd, and to outright and cataclysmic failure, that defines Phoenix’s finest work. There used to be a germ of self-loathing at the heart of his acting: “The reason why I keep making movies is ’cos I hate the last thing I did,” he said in 1999. “I’m always trying to rectify my wrongs.”

Nearly 20 years later, he had moderated his tune if not quite changed it: “The great thing about film is that you get to make mistakes,” he said last year. James Gray has noted the change, and the improvement, in the two decades they have been making movies together: back when they shot The Yards in 2000, he has said, “[Phoenix] didn’t have full control of his instrument. He was like an Olympic diver who didn’t know the formal rules of the Olympics yet.” After that, “he began to understand, frankly, that there weren’t limits, and he started to become fearless”.

Her (2013)

The livid, lapel-grabbing, Francis Bacon-esque character studies such as Joker, The Master and You Were Never Really Here may inevitably attract the most attention, but the level of nuance in some of his gentler performances – in Gray’s Two Lovers, where he plays a suicidal introvert still living with his parents yet not quite ready to relinquish hope, and in Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), as a lonely office worker who falls in love with his computer operating system – is just as deserving of study.

He couldn’t have played Freddie Quell in The Master had he not acquired that fearlessness Gray talks about. No actor afraid of mockery would have adopted that lumbering physicality, the shoulders bent so far forward that they almost clink together under his chin, or those blasts of corrosive laughter which explode from one side of his mouth, while the other side is clamped shut, rendering his speech almost incomprehensible.

The Master (2012)

As the private eye ‘Doc’ Sportello in Inherent Vice, he goes to the other extreme, not sinking into brute inarticulacy but advertising every internal outlandish reaction. It’s one of US cinema’s most joyously cartoon-like performances – like Jim Carrey in The Mask (1994), only without the aid of CGI. (It helps to think of the movie as a live-action Looney Tunes: no wonder people keep asking, “What’s up, Doc?”) Wacky physical asides hidden from the rest of the characters provide the equivalent of an interior monologue to which only the audience has access. Being the more high-minded of the two Anderson films, The Master was always going to be the better regarded, but both performances show Phoenix mapping out and inhabiting a physical world through performance.

Inherent Vice (2014)

His willingness to be laughed at sets him apart from his peers, and it’s one of the reasons that Arthur Fleck is such a perfect role for him, demanding as it does an actor who doesn’t distinguish noticeably between comedy and horror. Perhaps that’s how he has come to tolerate, or rationalise, the same excesses of Hollywood against which he once railed. “Joaquin Phoenix isn’t here tonight,” announced Tina Fey at the Golden Globes in 2015, “because he has said publicly that awards shows are ‘total and utter bullshit’ – oh, hey Joaquin! There he is.”

Cut to Phoenix, with that familiar smile, half shameless, half sheepish.

It has become quite the sport to look out for him in the audience at these shows. Not because he is bound to win (that rarely happens, though Joker will surely change all that) but because there is a feeling that he has made peace with the self-congratulatory tendencies of a profession that has in the past caused him visible discomfort, and is able to do great work nevertheless.

At the Independent Spirit Awards earlier this year, the host Aubrey Plaza looked out into the crowd and said: “Joaquin Phoenix is here from his ‘Beard’ trilogy: I’m Still Here, You Were Never Really Here and the upcoming Sir, You Cannot Sleep Here.” Cue another cutaway to the Phoenix grin.

Comedy is never far from even his most serious performances, so it’s no wonder there was widespread laughter at an industry showcase I attended a few years back, where early footage from Mary Magdalene (2018) included the announcement: “And starring Joaquin Phoenix as Jesus!” There was something so comically right and incongruous and pompously Hollywood about the idea of the son of God being played by a man who once fell off the stage while rapping in Las Vegas. (Sadly, the movie turned out not to be a joke.)

It’s a sign of how far Phoenix has come that there is scarcely any need now to print his name phonetically (see everything written about him until 2010) or to point out that his family fled the religious cult Children of God and drew appreciative crowds by busking and dancing on the streets, or that several of his siblings pursued successful acting careers – the Guardian referred to them in 1997 as “Birkenstock Barrymores” and in 2018 as “Haight-Ashbury von Trapps”.

Plenty of serious admirers of his acting don’t even know that he had a spectacularly gifted older brother, River Phoenix, whose death from a drug overdose he witnessed in 1993, and whose career it seemed for the longest time Joaquin would struggle to outstrip.

The brothers have their similarities. Both exhibited a flashpoint intensity, able to turn on a dime from larky to electrifying, and both have had Richard Harris as a screen father (River in Sam Shepard’s 1993 Silent Tongue, Joaquin in Gladiator). There’s a nice irony in the fact that it was River who lured Joaquin back from his first retirement by forcing him to watch repeatedly a VHS copy of Raging Bull (1980) – and that it is now Robert De Niro who not only provides one of the main inspirations for Joker but who also stars in the movie as an unctuous TV host Arthur idolises.

The Joker (2019)

But Phoenix has a quality that even De Niro lacks: a willingness, even a compulsion, to skate on the brink of the ridiculous. It’s no stretch to hold Phoenix in the same high regard as Daniel Day-Lewis, another two-time Paul Thomas Anderson leading man, and Joker proves every bit as much as his bestial, rampaging work in The Master that he is Day-Lewis’s equal in emotional and physical rigour.

The one element that sets him apart from the senior actor, though, is his willingness to mess up. He’s Marina Abramovic with a beard, the man Shia LaBeouf dreams of being, Christian Bale with a sense of humour, and the nearest A-list acting will ever get to Andy Kaufman. If De Niro and Day-Lewis walk the tightrope, Phoenix does so with his trousers down and egg on his face. In Joker, he dares us not only to laugh but to push beyond that response, to the fear that lurks behind it.

-

The 100 Greatest Films of All Time 2012

In our biggest ever film critics’ poll, the list of best movies ever made has a new top film, ending the 50-year reign of Citizen Kane.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.