Web exclusive

Gone Girl (2014)

The 52nd edition of the New York Film Festival – the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s annual jamboree, based in and around the south end of Manhattan’s well-heeled Upper West Side – represented the first chance for New York audiences to catch up with some major films that made the rounds at earlier high-profile festivals like Cannes, Venice and Toronto; these included Bennett Miller’s Foxcatcher, Mia Hansen-Løve’s Eden, David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars, the Dardenne brothers’ Two Days, One Night and Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner.

26 September-12 October 2014 | USA

The NYFF did, however, score a handful of notable world premieres. The first – David Fincher’s polarising potboiler Gone Girl – was a solid pick for opening night, particularly from a visibility standpoint. This sleek version of Gillian Flynn’s best-selling battle-of-the-sexes novel immediately set social media ablaze, and must have launched close to a hundred (and counting) thinkpieces arguing over whether it was misogynistic, a comedy, trash, or if you could sneak a glimpse of Ben Affleck’s penis.

I, for one, couldn’t get past Fincher’s sallow harnessing of the material’s sordid cynicism, and would have enjoyed it more had it been directed by, say, John Waters, or shared more in common tonally with Eating Raoul (1982), Paul Bartel’s riotously tacky satire of bourgeois coupledom. That said, Jeff Cronenweth’s slickly glaucous cinematography is a joy, Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor’s creepy/loopy score danced around my mind for hours afterward, and Tyler Perry – better known as the indefatigable star/auteur of such films as The Diary of a Mad Black Woman (2005) – all but steals the show as a brash criminal defence lawyer.

It’s also worth mentioning the post-film press conference in which Fincher repeatedly interrupted his bemused cast members by anxiously shouting “Spoiler!”, until it was pointed out to him by chair (and NYFF programmer) Kent Jones that the audience had just seen the film.

Inherent Vice (2014)

The festival’s second major world premiere – Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice – was also its hottest ticket: I was among the snaky throng queuing for hours in the rain for the Saturday-morning press screening at the Walter Reade Theater. This apparently faithful adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s shaggy noir novel from 2009 (which I’ve yet to read) is a melancholic comedy, and Anderson’s sixth consecutive film to prominently feature a California setting: in this case, a Los Angeles reeling from the Manson murders, and on the cusp of major physical change at hands of rapacious land developers. It’s becoming increasingly clear that the complex topography, histories and psychological mores of this vast state are as much a specific driving factor for the director’s vision as anything else.

Set in 1970, the year of Anderson’s birth, Inherent Vice stars a crumpled Joaquin Phoenix as the sweet-natured, mutton-chopped gumshoe ‘Doc’ Sportello, who finds himself inveigled in a knotty quagmire involving, among many other variables, a missing girl, insane dentists and a Jewish magnate with Nazi sympathies. Amid this pot-riven haze, clear stylistic and thematic touchpoints emerge, including Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) (though Sportello makes Elliot Gould’s Marlowe look like the model of consistency), the deep moral rot of Chinatown (1974) and the warm-glow madcap of the Coens’ The Big Lebowski (1998).

The pacing of this long, languid film (it clocks in at 148 minutes) vacillates wildly, as does its tone, which flits between menace, pathos and ribald slapstick, often in the same scene. It is, however, easily Anderson’s loosest, most limber work since 1997’s Boogie Nights – a refreshing change of pace after the heavy weather of There Will Be Blood (2007) and The Master (2012). Though I sometimes found myself more bemused than truly engaged, it’s a dense, textured work that I suspect will reward repeat viewings. Incidentally, it was one of a tiny handful of films to screen on 35mm at the festival, meaning that its period setting was not the only factor lending it a throwback vibe.

Like Inherent Vice, the NYFF’s other major coup, Laura Poitras’ riveting documentary Citizenfour, focused on a sensitive lone figure enmeshed in an opaque network of conjecture and nefarious conspiracy. But there’s nothing fictional about its subject: then-29-year-old whistleblower Edward Snowden, who made global headlines in June 2013 upon leaking a fount of classified information from the National Security Agency (NSA).

Citizenfour (2014)

Following an opening patchwork of contextual scene-setting in which Poitras stealthily, and brilliantly, nails the tricky task of outlining the key players in (and opponents of) the US government’s covert programme of mass surveillance of its everyday citizens, Citizenfour changes tack. It segues into a remarkably intimate record of the eight-day spell in which the courageous, quietly confident Snowden, ensconced in the upper reaches of a skyscraping Hong Kong hotel, steeled himself for his actions and their ensuing fallout. Despite Poitras’ incredible level of access (Snowden approached her and journalist Glenn Greenwald in the first place to convey his information) the director, who had to edit the film in Berlin to avoid US government harassment, remains an unobtrusive, almost spectral presence.

There are many reasons Citizenfour is so remarkable – it is, for one, a superbly made, globe-spanning techno-thriller in its own right: John le Carré by way of William Gibson – but I left the cinema feeling genuinely rattled, most of all, by its throat-grabbing verisimilitude. It’s difficult to think of a recent documentary in which the stakes have been higher, its real-life relevance so undeniable. At the risk of making lofty statements, Citizenfour could easily come to be viewed as one of the defining films of its era. It remains to be seen how the Obama administration will react to this chilling, piercingly transparent document. It’ll surely have to react somehow.

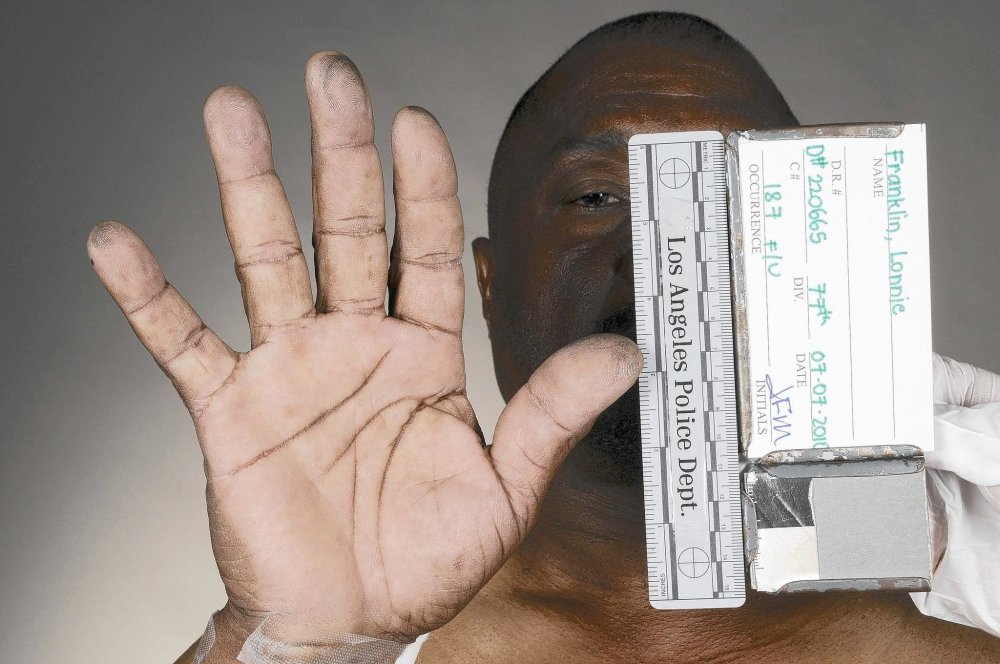

Tales of the Grim Sleeper (2014)

The NYFF boasted a strong documentary slate in general. If Citizenfour cast the American government as compulsively intrusive and invasive, then the opposite was true for Nick Broomfield’s Tales of the Grim Sleeper. The British director’s impressive, but extremely upsetting, latest tells the story of a serial killer in South Central Los Angeles who was essentially left, with little interference, to murder scores of African-American women – many of them impoverished, crack-addicted sex workers – for more than 20 years. As the injustices and unpalatable details of this appalling case pile up, a depressing portrait emerges of a microcosm of a nation hopelessly divided among class, race, gender and economic lines.

Another British filmmaker, Philip Warnell, provided one of the surprises of the festival with Ming of Harlem, which screened in the Projections strand (formerly Views from the Avant-Garde). It’s based on the weird-but-true story of Harlem resident Antoine Yates who, until 2003, kept a tiger in the fifth floor of his spacious tower-block apartment.

Ming of Harlem (2014)

Any notions that Warnell would play the material for tabloid yucks evaporated along with an opening epigram from Jacques Derrida meditating on the nature of man and beast. The film itself is a curiously haunting blend of observational documentary (Yates, whom Warnell interviews while driving around Harlem, is a sensitive, complex character) and reconstruction: Warnell actually built a replica of the apartment for a tiger to prowl around in a hypnotic, if lengthy, digressional sequence.

More straightforward, but no less entertaining, was Gabe Polsky’s Red Army, a riotously fun record of the fortunes of the Soviet Union’s all-conquering ice hockey team in the Cold War-riven 1980s. Polsky’s film has all the ingredients – including a compelling central figure (Slava Fetisov, the taciturn but dry-witted star player), swashbuckling style, and plenty of humour to complement the political exegesis – to make it a breakout hit.

Red Army (2014)

The NYFF closed, fittingly, with Alejandro González Iñárritu’s metafictional, metaphysically-inclined melodrama Birdman, which features the excellent Michael Keaton as Riggan Thompson, a former action-movie superstar trying to make it as the writer-director-star of a Raymond Carver play on Broadway. Birdman is immediately notable for its startling aesthetic conceit: it’s (very) subtly edited to make it seem like it’s all taking place in one long tracking shot – a gimmick, for sure, but a good one, particularly with Emmanuel Lubezki, the grand master of hypnotic floatiness, on DoP duty.

With its sharp humour and ensemble cast of bickering backstage thesps (Naomi Watts and Edward Norton are particularly good), Birdman initially seems atypical territory for Iñárritu, but it ultimately winds up, perhaps to its detriment, in the director’s more familiar register of bombastic, male-centric self-flagellation. That said, it’s never less than absorbing, and proved a fitting way to end the festival: its most memorable, bravura scene depicts a flustered Keaton tearing through New York’s bustling Times Square in his tighty whiteys – surely a sequence that will find itself spliced into iconic New York movie compilations for centuries to come.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.