Web exclusive

The 10th Victim (La decima vittima, 1965)

While London’s repertory scene is sturdy, with collectives like A Nos Amours bringing under-appreciated gems like Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó to enthusiastic cinephiles, rep cinema programming in New York is even more rich and varied. Anthology Film Archives, MoMa, Film Forum and Brooklyn’s BAMcinematek provide a respite from the seemingly-endless barrage of sequels, prequels and literary adaptations that saturate modern mainstream Hollywood. In the spirit of summer counter-programming, Nicolas Rapold, Senior Editor of Film Comment magazine, put together a weeklong retrospective of rare science fiction from central and Eastern Europe at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theatre. Strange Lands: International Sci-Fi spanned 30 years (1958-88) and five countries (from Italy to Poland and the then-East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Soviet Union), and an impressive ten of the 11 films were screened from 35mm prints.

Strange Lands: International Sci-Fi

22-28 August 2014 | Film Society of Lincoln Center, New York, USA

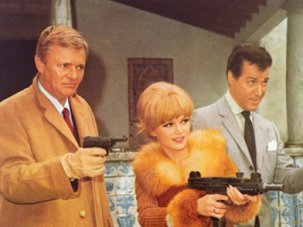

Satires like In the Dust of the Stars (Gottfried Kolditz, 1977), Kin-Dza-Dza (Georgi Danelia, 1986) and The 10th Victim (Elio Petri, 1965) offer a comedic approach, all the while grappling with the sub-genre’s themes of class warfare, paranoia and political repression. Kin-Dza-Dza is an absurdist comedy from the perestroika era about cynical construction worker Uncle Vova (Stanislav Liubshin) and a young violinist who find themselves unwillingly transported to Plyuk, a barren desert of a planet where matches are more valuable than money and spaceships resemble a cross between a Dalek and Howl’s Moving Castle. The interplanetary violence that takes place as Vova and the fiddler struggle to get to grips with Plyukian cultural customs is played for laughs, a bumbling pantomime of the Soviet Union’s very real political revolts during the Cold War – though with none of the lasting consequences.

Kin-Dza-Dza (1987)

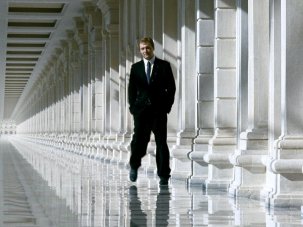

Equally enjoyable is Petri’s The 10th Victim (pictured at top), a stylish 60s romp that centres on a public manhunt called the Big Hunt, a futuristic sport enjoyed as much by its fame-hungry participants as their voyeuristic onlookers. “Why control the births when you can control the deaths?” reads a voiceover whose winking tone masks its paranoid sentiment. When two top assassins (Bond bombshell Ursula Andress and the suave Marcello Mastroianni) are pitted against one another, they discover that their inevitable attraction complicates the game. It is suggested that their final fight be televised – and Andress’ Meredith handsomely remunerated by her corporate sponsor if she wins.

A neat satire of burgeoning postwar consumer culture, The 10th Victim taps into the contemporary cult of reality television, leaving one wondering if Suzanne Collins was familiar with Petri’s film before she wrote The Hunger Games. With its breathy, jazzy score, mod fashion (see Meredith’s backless, batwing pink pantsuit) and gentle digs at both po-faced neo-realism and the transparent vulgarity of America’s celebration of lowbrow entertainment, the film plays up the differences between Italian and American culture to amusing effect.

Eolomea (1972)

Many of the other films in Rapold’s eclectic selection, like Eolomea (Herrmann Zschoche, 1972), Morel’s Invention (Emidio Greco, 1973), The End of August at the Hotel Ozone (Jan Schmidt, 19676) and Aleksandr Sokurov’s Days of Eclipse (1988), are characterised by a misanthropic feel. The first two are, at their cores, stories of heartbroken men who are more preoccupied by earthly pleasures than scientific discovery. Eolomea’s Daniel Lagny (Ivan Andonov) spends his days as a cynical cosmic drifter mooning after Professor Maria Scholl (Cox Habbema), an inquisitive, sombre blonde he left on Earth; Morel’s Invention sees a rugged castaway (Guilio Brogi) trapped on the wrong side of the veil while lifelike projections of his former lover (Anna Karina) run on a loop for all eternity. Said invention has been created by handsome mad scientist Morel (John Steiner) under the guise that it enables him to give his guests “a pleasant eternity” – an eternity that does not include our nameless castaway. What’s most sinister about Morel’s Invention is the duplicitous manner in which Morel traps his victims, exploiting their individual rights and experimenting on their psyches without invitation – a threat that feels all too familiar given recent unsolicited social experiments on Facebook.

“The women must not know – hysteria is contagious,” warns Morel. However, from In the Dust of the Stars’ commanding female captain to the pack of wild she-wolves that roam the dystopian landscape of The End of August at the Hotel Ozone, women seem to dominate many of Strange Lands’ imagined futures. My highlight of the weeklong series was another female-centric feature – Ulrike Ottinger’s Freak Orlando (1981). Chicagoan critic Dave Kehr describes Ottinger as “a one-woman avant-garde opposition to the sulky male melodramas of Wenders, Fassbinder and Herzog.”

Freak Orlando (1981)

Based on both Todd Browning’s Freaks and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Freak Orlando journeys through the fictional Freak City, tells ‘The Little Theatre of the World’ in five surreal episodes. An ambitious feminist epic, it tracks the history of the world “including the errors, the incompetence, the thirst for power, the fear, the madness, the cruelty and the commonplace” – but really, it’s the story of woman’s struggle in a man’s world. Tourists in plastic anoraks flank a gothic cobbler (Delphine Seyrig), furious that their ‘mythological shoes’ don’t fit; a bearded woman performs the apocalypse like a slot machine, only pausing to sip her dry Martini. Ottinger takes Morel’s fear of the hysterical woman and flips it; prefacing that a broken heart can make highly emotional women grow beards, the film contains a multitude of bearded women, punishing them for their transgressive feelings and features.

The heroine – or hero – of this gender-bending carnival is Orlando (Magdalena Montezuma), a lizard-skinned freakshow in an Annie Hall-esque man’s suit who is beloved by the decadent denizens of Freak City. There’s an ugly contest, conjoined twins in flapper dresses, dancing Playboy bunnies and a long line of male flagellates – but in Ottinger’s community of freaks, “pain shared is almost half a pleasure.”

This diverse taste of international sci-fi certainly has this writer very excited for the BFI’s own Sci-Fi: Days of Fear and Wonder season this autumn.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.