Web exclusive

To Singapore, with Love

Everyone agrees, the Dubai International Film Festival has come a long way since it was founded ten years ago. Dubai itself may be a paradis artificiel of a kind that Baudelaire never dreamt of – it’s been conjured out of the desert sands in just four decades – but it remains an Arab Emirate, governed by Muslim codes of decorum and modesty.

Dubai International Film Festival

6-14 December | United Arab Emirates

I spent nine days there in December 2013, chairing the jury for the Muhr AsiaAfrica Documentary Award, and arrived with a head full of rumours I’d heard about censorious constraints on the festival’s programming. Apparently it’s true that the programmers had to be careful not to offend local sensibilities in the early years, but local sensibilities have clearly moved on. The 2013 gala screenings included 12 Years a Slave, restricted to over-18s (“contains brief sex scene, coarse language, death, extreme violence, male nudity, nudity and rape scene” warned the catalogue), but nobody protested and the packed house applauded respectfully. The only censorship I noticed during my stay was in the Gulf News: episodes of Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury strip which satirised President Karzai and American tactics in Afghanistan were replaced by more anodyne flashbacks to earlier strips.

The festival pays its dues to Hollywood by screening everything from kiddie animation to current Oscar-bait (it closed with David O Russell’s gruelling American Hustle, presumably because Robert de Niro’s gangster character gets to speak lines in Arabic), but it has an overriding mission to kick-start more Arabic film production and a richer Arabic film culture. So the 10th edition opened with Hany Abu Assad’s Cannes winner Omar, subsequently the winner of the Dubai Grand Prix, and the selection overall was dominated by Arab, Asian and African cinema.

The ten documentary features my jury was asked to look at were mostly Asian. A couple of them must have scraped in to make the geographical representation broader (I could have done without the plod through the history of the Indonesian film archive and the high-gloss, retro-leftist account of labour activism in Korea Telecom) but we found plenty to admire and enjoy.

Wukan: the Flame of Democracy

Our Special Mention went to Lynn Lee and James Leong’s Wukan: the Flame of Democracy (Wukan: Minzhu zhi Guang), a rumbustious look at the struggle to make democracy work at a grassroots level in a village in southern China. Protestors manage to oust vested interests in a local council election, but then run foul of entrenched bureaucracies higher up the system; disillusionment sets in and resignations follow. The film dampens hopes for grassroots-led reform of China’s politics, but James Leong tells me in an email that recent developments in Wukan are warranting a sequel.

Our Best Director prize went to Tan Pin-Pin for To Singapore, with Love, her group-portrait of some of the activists and intellectuals who were driven out of Singapore in the 1960s and 70s – some after periods of imprisonment – because they dared to argue with Lee Kwan Yew’s patriarchal diktats. The film uncovers a history that’s been suppressed, not least in Singapore itself, helping to explain why Singapore still today runs on puffed-up nationalism, social control and censorship; Tan may well have a hard time getting her film shown at home.

Many of her interviewees are nostalgic for the place they had to leave behind, as exiles often are, but the star of the film is UK-based Dr Ang Swee-Chai, the widow of a leftwing activist who died in exile, and she’s impressively clear-minded about her own situation and about Singapore’s wretched human rights record. Dr Ang has transcended the ‘exile mentality’ by volunteering to work in hospitals in Palestine; she’s even more of a heroine than Tan Pin-Pin is herself.

My Red Shoes

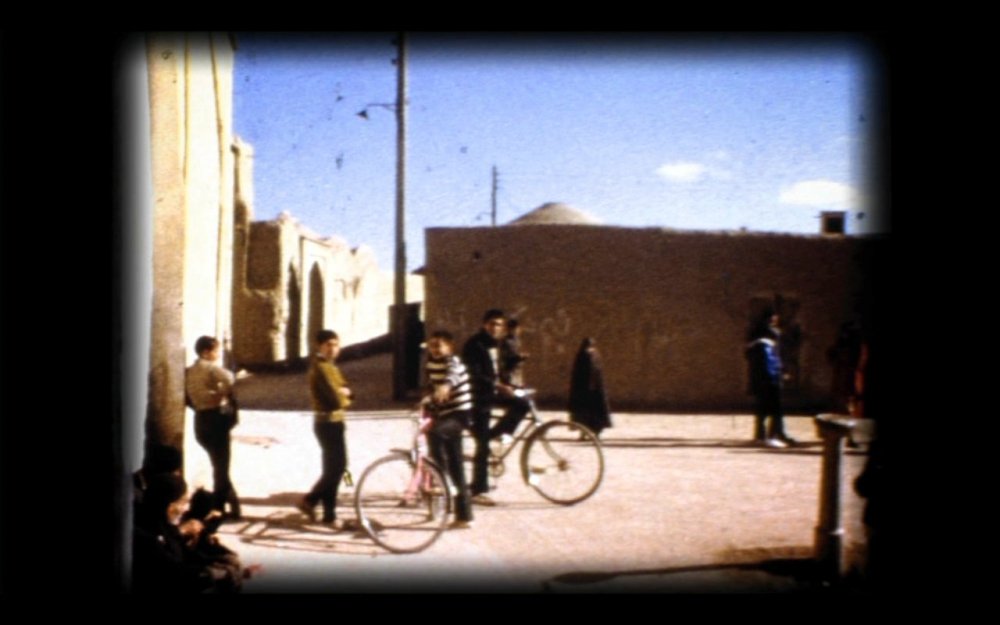

More exploration of the experience of exile in our Special Jury Prize winner My Red Shoes, in which Sara Rastegar discovers how and why her parents Kaveh and Fariba fled from Iran soon after the Islamic Revolution that brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power. They’d been Marxist students opposed to the Shah, so greeted his overthrow with great optimism – only to find themselves on the wrong side of Islamofascism. Imprisoned and tortured, Kaveh managed to escape to France, eventually followed by his wife and then-young daughter. It’s a film in which the personal really is political, and vice versa; Rastegar uses old home movies to both show the domestic, quotidian routines which linked life in Iran and France and explore the aching spiritual void which follows a cruel political disillusionment.

Juries have a tendency to judge documentaries on the ‘worthiness’ of their subjects, but I don’t think we were guilty of any such failing when we gave our Best Film prize to The Horses of Fukushima (Matsuri no Umi) by Matsubayashi Yoju. Scouting inside the ‘exclusion zone’ around the crippled Daiichi Nuclear Plant in Fukushima, the director came across a stable of horses wounded in the tsunami; his film focuses on one horse in particular, a failed steeplechaser called Miller’s Quest, which was being fattened up for sale as horse meat when the disaster struck.

Its injuries left it with an inflamed and embarrassingly distended penis, but its somewhat idealistic owner chooses to help it recuperate enough to take part in the Soma Nomaoi, a local Shintoist horse festival. The convalescence includes a restorative stay in the northern island of Hokkaido. Matsubayashi initially approaches the horse with understandable caution, but as it gets used to having him around he also gets more comfortable being near it, a change reflected in his fluid, lyrical camerawork.

The Horses of Fukushima

Shot mostly in the ‘exclusion zone’, the film is a paean to resilience and strength – not only of the horses, but also of the men who look after them. It’s also by some way the most original and moving of the many documentaries made in the aftermath of Japan’s worst peacetime nuclear disaster.

I had an extraordinary experience with Matsubayashi-san in Dubai. We needed to get from the multiplex in the Mall of the Emirates to the hotel one day, and decided to share a taxi. But the driver refused us – too troublesome, too much traffic – until Matsubayashi started talking to him in fluent Pashtun, having guessed correctly that he was an Afghan. It turned out that Matsubayashi had spent a year in Afghanistan a while ago, three months of it learning Pashtun. He’s now working on Brazilian Portuguese, to prepare for his next film – about émigrés from Fukushima in Brazil.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.