Web exclusive

Vertigo (1958)

“You’re not doing it right, you’ve got to cut it in two. That’s it. Bite it close to the bone. That’s the best part.”

Francis Coppola is instructing me how best to eat the Argentine rib steak on the menu in the Zoetrope restaurant he owns. The lethal-looking gaucho knife provided had me slicing the succulent flesh too warily. I’m a little dazzled because Coppola just walked in unannounced while we were eating.

My second day in San Francisco and I’m already, so to speak, having an audience with the pope. He’s there to get a haircut across the street. I’m there with Tom Luddy of Zoetrope and the Telluride Film Festival to lunch with Stig Bjorkman, the Swedish director and writer who’s often contributed to S&S; we’re joined by novelist Thomas Sanchez (Day of the Bees, Rabbit Boss, Zoot Suit Murders) and my friends Daniela Michel – who runs the Morelia Film Festival in Mexico – and James Ramey, a super-erudite literature academic and certified Nabokov nut.

Sanchez tells me about a friend of his who’s painstakingly restoring an apartment Dashiel Hammett (writer of The Maltese Falcon and other landmarks of hard-boiled crime fiction) lived in. The reason he’s telling me is because I’m already talking about ‘filmgrimages’ – an ugly neologism, I know, but the melding of ‘film’, ‘pilgrim’ and ‘images’ suits the peculiar excitement one gets from being in the real place where an adored film was shot.

Woman on the Run (1950)

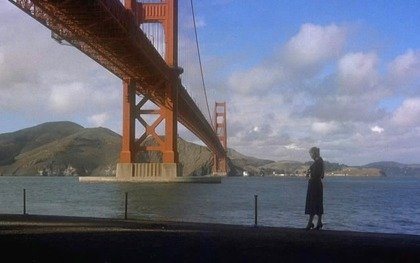

That morning Tom Luddy had been showing me around the city, starting with the sprawling farmer’s market on the Embarcadero, then a drive to the observation spot on the other side of the Golden Gate Bridge where Tom had not been for 20 years, and on to my first ever glance of the Pacific. I would soon see most of these sights again in a more film-related context. Tom is instrumental to so many things, but it’s Rachel Rosen, head of the San Francisco Film Festival (not the droid of the same name in Philip K Dick’s San Francisco-set Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), who’s responsible for me being in the city.

She and her colleagues invited me onto the New Directors jury, and put me up at The Fairmont, the hotel on Nob Hill where Hitchcock stayed when he made Vertigo (of which more later). The SFFF was the first ever film festival in the Americas and it retains its relaxed cinephile appeal by being perfectly judged on a human scale. I can’t write about our jury deliberations, except to say that I’m delighted that we gave the prize to Park Jung-bum’s excellent first feature The Journal of Musan. But what I can talk about is the opportunities the festival provides for filmgrimaging.

Much of San Francisco still looks like a film noir backdrop. Many of the steepled houses have a half-folksy, half-sinister look. The hilly nature of the terrain offers many dazzling prospects and vertiginous camera angles. I only experienced bright sunshine but I could feel the chill in the shadows and I heard a lot about the fog that comes in. High contrast black & white cinematography could find no better environment. There are two city tours conducted by the San Francisco Film Society’s estimable creative director Miguel Pendás. His expansive film noir tour takes in locales for Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952), Thieves Highway (Jules Dassin, 1949), The Sniper (Edward Dmytryk, 1952), Born to Kill (Robert Wise, 1947), Woman on the Run (Norman Foster, 1950), The Lineup (Don Seigel, 1958) and D.O.A. (Rudolph Maté, 1950), as well as others I will mention. The city also holds an annual film noir festival.

At World’s End: The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

We visit former nightclubs, the onetime Chinese telephone exchange, imagine the dark zone created by the raised freeway that once skirted the city, but happily was pulled down after the most recent earthquake. On Telegraph Hill we get out and take a look at the art deco apartment block where Lauren Bacall sheltered Humphrey Bogart and his bandaged head in Dark Passage (Delmer Daves, 1947). We go to World’s End where Orson Welles sees Rita Hayworth’s demise in The Lady from Shanghai (Welles – uncredited) and wish the amusement arcade with the hall of mirrors was still there. There was much more to the tour, but I don’t want to steal too much of Miguel Pendás’s terrific thunder.

Being a genuine psychiatric condition with specific symptoms, obsession is a generally misused term. Films noir, for instance, often have obsessive behaviour as their plot motor, but Hitchcock’s Vertigo is about the very illness of being possessed by a single idea, in this case that the presence of dead person can be recreated through obsessive reconstruction. (There are also, of course, obsessive elements to cinephilia itself and to the collector mentality evident in so many cinephiles). Miguel Pendas’s excellent and evocative Vertigo tour made Hitchcock’s film temporarily inescapable for me too – perhaps partly because S&S had recently published Miguel Marías’s about its continuing allure.

You can, if you wish, stay in the same room where, it is calculated, Judy, the seeming lookalike of Madeleine, lived in what is now the Vertigo Hotel (the Empire in the film). It costs nothing to pose in the parking bay of the glorious Brocklebank Apartments – the domicile of Gavin and Madeleine featured so strongly by Hitchcock. The tour’s people carrier swerved gamely down Lombard Street, known as the ‘crookedest’ street in the world, in order to reach Scotty’s apartment, with the obviously phallic Coit Tower in the background, where Madeleine is waiting to thank him for saving her from drowning: “I remember Coit Tower. It led me straight to you.” “That’s the first time I’ve felt grateful for Coit Tower,” he replies.

Judy/Madeleine/Carlotta at Fort Point in Vertigo (1958)

In the genuinely creepy Mission Dolores cemetery we’re told the fake Carlotta Valdez gravestone remained there for years after the filming until one night it disappeared. Miguel also shows us the tiny child’s gravestone Chris Marker filmed for Sans Soleil. Then it’s on to Fort Point, the most spectacular filmic view in the city. In Vertigo this view of the Golden Gate bridge – the scene where Madeleine jumps into the San Francisco Bay – seems somehow exaggerated, like a matte painting, but when you’re standing there beneath the bridge for real it looks exactly as it does in the film, an insane curve vanishing into the distance.

In the bus we begin to fantasise about other San Francisco filmgrimages: a Bullitt tour, a Dirty Harry tour. I suggest a kitsch Basic Instinct tour for which everyone must wear a figure-hugging green V-neck sweater in honour of the terrible one worn by Michael Douglas in the nightclub scene. As we’re laughing about this, the scene in Scotty’s apartment, after Madeleine has woken up there, comes up on Miguel’s laptop. Scotty is wearing a green V-neck – albeit over a crisp white shirt. Paul Verhoeven clearly knew what he was doing, but was it Michael Douglas who insisted on not wearing the shirt?

Back at the Zoetrope restaurant, Coppola is talking expansively and eloquently about his new passion for making lower-budget films that he can completely control and own (see, for instance, Nick Roddick’s Tetro interview in S&S July 2010). His argument is passionate and persuasive. I’m fascinated by the allure such freedom has for people in the later stages of their career, but I’m conscious that Daniela Michel and I have a jury film to see. So we have to end our fortuitous audience prematurely. I haven’t done much more than wave at Stig Bjorkman. I won’t find the time to meet Thomas Sanchez’s friend and see Hammett’s apartment. But that’s the thing about filmgrimaging: the activity never ends. There’ll be a next time. I hope.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.